Anoxia during a 4-hour window can lead to dominant and aggressive behaviour in zebrafish

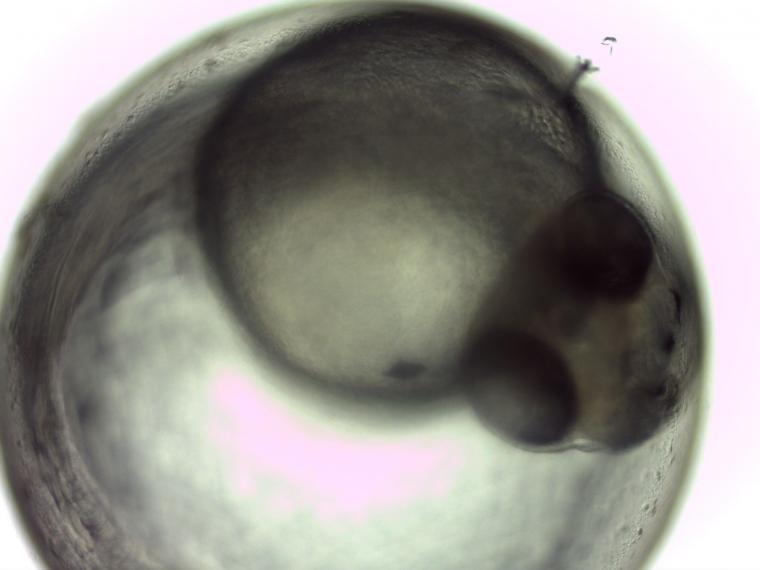

Earlier research had shown that zebrafish embryos could survive hypoxia (low oxygen) and even anoxia (complete absence of oxygen) during the first 24 hours which is quite a feat.

This piqued the interest of Prof. Nick Bernier and his students, Catie Ivy and Cayleigh Robertson who are now both PhD students at McMaster University under Profs. Graham Scott and Grant McClelland, respectively.

These researchers suspected there may be long-term consequences to anoxia exposure because the embryonic stage is when the fish are developing their stress responses and this question is becoming increasingly important as greater incidences of both anoxia and hypoxia are occurring in fish nursery habitats due to eutrophication and climate change.

They had previously isolated a critical development window of hypoxia and anoxia sensitivity in zebrafish embryos at 36 hours post-fertilization and used this window to test their hypothesis that acute anoxia exposure of 4 hours will change the stress response of zebrafish embryos reared to adulthood.

However, initial results showed that adults derived from anoxia-exposed embryos did not differ in their stress response to hypoxia relative to adults derived from control embryos.

The researchers then decided to expand on their hypothesis and tested whether anoxia had an effect on zebrafish at higher levels of brain responses (i.e. social interactions) and to their excitement, they found a significant response in their dominance and aggression behaviour.

Adults derived from anoxia-exposed embryos were dominant in 90% of the paired interactions – meaning they initiated more chases, received fewer bites and froze less often. These adults were also 60% more aggressive during the mirror aggression experiment where a mirror is placed in front of the fish to trigger aggressive responses such as biting.

Reduced gonadal aromatase expression (i.e. decreased estrogen) and increased testosterone levels were also observed in these zebrafish and may provide a causal explanation for these altered behavioural responses.

All their findings demonstrated that oxygen deprivation during a small but critical window during embryonic development can have long-lasting consequences on adult hormonal and behavioural responses.

Moving forward, the Bernier lab is continuing research on this critical development window and trying to mimic natural environments and relevant exposures to hypoxia and other stressors.