University of Guelph pathobiology professor Byram Bridle and history major Erik Campbell-Anton probably have never met. But when it comes to battling the COVID-19 pandemic, the professor and the student are united.

Before this spring, Bridle had focused on uses of vaccines for treating cancer. Then came the novel coronavirus. Along with pathobiology professors Sarah Wootton and Leo Susta, he adapted his research program to pursue a potential vaccine. In May, the trio of investigators received $230,000 in provincial funding to test four vaccines already developed in University labs.

Bridle expects that their combined effort, involving about a dozen researchers including students and post-docs, will yield a leading candidate in the race among some 120 Canadian projects to develop an effective vaccine. “I feel empowered to do something about a world problem,” he says. “We’ve been overwhelmed by the number of applications we’ve had from people to join our research group. This is an opportunity for scientists to do something where the science really matters. It’s an opportunity to apply the expertise developed over the course of our careers in a very practical way.”

Following a similar impulse to help where he could, Campbell-Anton took a front-line job this spring at an assisted-living centre in St. Thomas, Ont., working alongside his grandmother and two aunts who are staff members there. He wanted to help alleviate pandemic-induced stress among staff and residents, not to mention giving himself a sense of purpose. “We are going through an extremely difficult time as a society, with COVID-19 taking a toll on everyone, whether it be physical or mental,” says Campbell-Anton. “I felt rather useless sitting at home doing nothing.”

Following a similar impulse to help where he could, Campbell-Anton took a front-line job this spring at an assisted-living centre in St. Thomas, Ont., working alongside his grandmother and two aunts who are staff members there. He wanted to help alleviate pandemic-induced stress among staff and residents, not to mention giving himself a sense of purpose. “We are going through an extremely difficult time as a society, with COVID-19 taking a toll on everyone, whether it be physical or mental,” says Campbell-Anton. “I felt rather useless sitting at home doing nothing.”

Bridle and Campbell-Anton are just two examples of how U of G faculty, staff and students have adapted their studies, expertise and aptitudes to address numerous aspects of the pandemic, from community well-being to research. In the process, they have demonstrated several truisms about the University as a whole. U of G’s long-standing foundation of research and innovation and its renowned community-mindedness meant that members were prepared to bring varied strengths to bear against the novel coronavirus. If the institution serves to improve life and to lift communities, paraphrasing president Franco Vaccarino, then campus members found many ways to demonstrate those values during this year’s unprecedented crisis.

Campbell-Anton wasn’t the only student to don scrubs and head to work in a long-term care facility this spring. In April, Jeff Vdovjak, a kinesiology student at the University of Guelph-Humber, began duties as a personal support worker at a long-term care home in Toronto. Having done humanitarian work abroad, he felt compelled to support health-care workers and fill a staffing gap. “Canada is in need and I am happy I can help,” Vdovjak says. “Our seniors are vulnerable, and they are disproportionately affected by COVID-19. In past generations, Canadians had to fight wars. I’d like to be of help now in this crisis.”

Elsewhere, U of G and its students, faculty and staff banded together in various crisis-relief efforts. In mid-April, the University donated more than 100,000 pairs of nitrile gloves and 2,300 N95 masks, as well as isolation gowns and sanitizer, to local public health authorities. Coordinated by Melissa Horan, U of G’s Wellness@Work coordinator, and Alison Burnett, director of Student Wellness Services, the campaign collected supplies from across campus, including lab and animal facilities as well as the University’s Hospitality Services and Athletics departments. The personal protective equipment was distributed to local hospitals and health care facilities through the Guelph Community Health Centre (GCHC).

That donation followed an earlier University shipment of 10,000 N95 masks collected from labs across campus to Wellington Dufferin Guelph Public Health. As well, the Ontario Veterinary College provided two ventilators to local health care centres to help alleviate shortages of much-needed equipment. Explaining that the donations were intended to help front-line workers care for those in need, Don O’Leary, vice-president (finance, administration and risk), says, “The University is committed to doing all we can to support the fight against COVID-19.”

By spring, U of G chefs normally would have been preparing meals for students and preparing menus for summer conferences on campus. Instead, the University’s kitchens were busy putting together 500 meals a day to help feed Guelph’s most vulnerable citizens during the pandemic.

Hospitality Services is supporting a new program launched by The SEED, a not-for-profit organization at the GCHC. The program provides food for people identified by city, county and public health officials as most deeply affected by the pandemic because of isolation or lack of money. By late May, U of G kitchens were providing about 3,000 meals a week and had prepared more than 15,000 in total. Noting that some U of G students would likely be among the recipients, Ed Townsley, executive director of Hospitality Services, says, “It is extremely gratifying to help other community members during this time of need. It feels good to be working with a community organization like The SEED.”

Hospitality Services is supporting a new program launched by The SEED, a not-for-profit organization at the GCHC. The program provides food for people identified by city, county and public health officials as most deeply affected by the pandemic because of isolation or lack of money. By late May, U of G kitchens were providing about 3,000 meals a week and had prepared more than 15,000 in total. Noting that some U of G students would likely be among the recipients, Ed Townsley, executive director of Hospitality Services, says, “It is extremely gratifying to help other community members during this time of need. It feels good to be working with a community organization like The SEED.”

Sparked by Clarissa Shepherd, coordinator of the Guelph Student Food Bank, that partnership was just one example of University efforts to ensure that students and the local community had access to affordable food. In one week in late March, Hospitality Services donated $32,000 worth of food to local food banks and assembled 75 hampers to be delivered to students still living in residence.

Although most students left campus residences under COVID-19 prevention measures implemented in March, some 170 students were unable to return home. They were moved to townhouse residences on campus with access to kitchens, where Student Housing equipped the students with kitchen supplies. “We are ensuring these students not only have suitable food and housing, but we are also providing them with support through virtual connections and programming to help with the feelings of anxiety and isolation,” says Irene Thompson, director of Student Housing.

Those supplies were funded through alumni donations to the University’s Highest Priority fund that supports emerging opportunities and urgent needs across campus, says Lisa Hood, associate director, annual fund, with Alumni Affairs and Development. She says the fund “offers the president and administration the flexibility to respond quickly at times like this, as well as with whatever the emerging needs are in six weeks or six months, which is important at a time of such rapid change.”

This year, U of G also made temporary housing available in campus residences to health-care workers, emergency responders and others affected by the COVID-19 crisis. That measure enabled those workers to live apart from their families while caring for patients or providing other services, says Carrie Chassels, vice-provost (student affairs). “U of G is a key member of the greater Guelph community, and we are all in this together,” says Chassels, who heads the University’s Community Support Working Group. “We are committed to doing our part to help our community during this incredibly challenging time.”

As one of Canada’s top research-intensive universities, U of G has also brought its research and scholarship to bear on wider aspects of this pandemic. Overall, that scope is embodied in the range of projects – 51 in all – to gain support this spring from the University’s new Research Development and Catalyst Fund. Developed in just six weeks, the program awarded nearly $700,000 to U of G researchers for projects intended to reduce the disease spread, prevent or treat COVID-19, and understand its effects on people and communities.

Each project received up to $10,000, with matching support from departments, colleges and private donors. “I’m tremendously pleased with the response to this funding program,” says Malcolm Campbell, vice-president (research). “Clearly, our researchers – and indeed the entire University community – are eager to lend our expertise and leadership to the vitally important pursuit of reining in this pandemic and thereby improving life.”

With a vaccine still months if not years away, finding effective ways to treat the disease and stem its spread is vital. In the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Prof. Wei Zhang is targeting protease molecules that enable the virus to hijack the body’s immune response. Similar mechanisms work for the coronaviruses that cause SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome); earlier as a post-doc at the University of Toronto, he helped develop inhibitor molecules for the MERS-causing virus. “We need to optimize these molecules to demonstrate their efficacy in the cell,” says Zhang, who is working with a U of T team on the $900,000 project funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). As with the vaccine project, this protein engineering work may lead to a treatment platform to help combat not just the COVID-19-causing virus but other potential health threats in future.

Treating the disease among infected people is one thing. Reducing its spread is another. In another instance of adapting existing research for COVID-19, food scientist Keith Warriner is using an innovative approach for decontaminating fresh produce to sanitize N95 masks for health-care workers battling the pandemic – an adaptation refined by post-doc Mahdiyeh Hasani. A Beamsville, Ont., company that markets the produce-cleaning technology is now making units that run batches of masks like an airport X-ray scanner, sanitizing up to 800 masks in an hour. “Once I heard about the mask shortage and the need to decontaminate them, my thought went right to this. It ticks all the boxes and I knew the research could make a difference,” says Warriner, who also spoke to media this spring, cautioning against using gloves as a substitute for handwashing.

Treating the disease among infected people is one thing. Reducing its spread is another. In another instance of adapting existing research for COVID-19, food scientist Keith Warriner is using an innovative approach for decontaminating fresh produce to sanitize N95 masks for health-care workers battling the pandemic – an adaptation refined by post-doc Mahdiyeh Hasani. A Beamsville, Ont., company that markets the produce-cleaning technology is now making units that run batches of masks like an airport X-ray scanner, sanitizing up to 800 masks in an hour. “Once I heard about the mask shortage and the need to decontaminate them, my thought went right to this. It ticks all the boxes and I knew the research could make a difference,” says Warriner, who also spoke to media this spring, cautioning against using gloves as a substitute for handwashing.

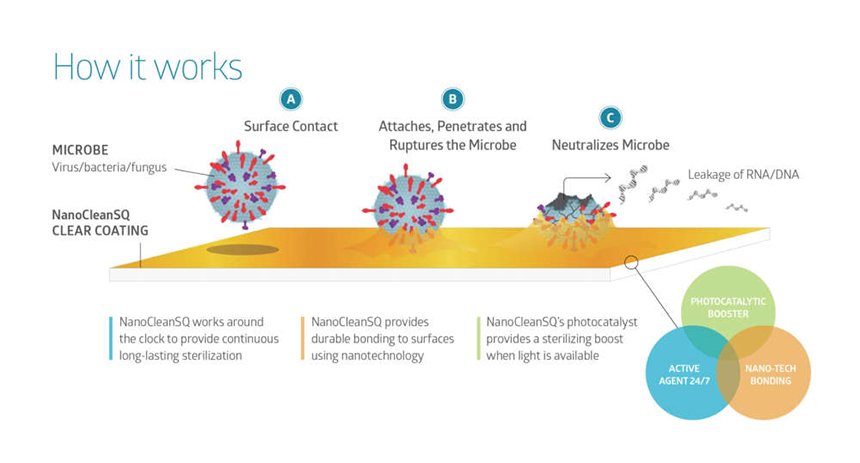

Adapting technology against the coronavirus also spurred engineering professor Bill Van Heyst. Along with EnvisionSQ, a company based in Guelph, he had developed a light-activated process for cleaning smog, industrial pollutants and other substances from air. Using federal funding earmarked for producing technologies to fight COVID-19, the team developed a self-sterilizing coating called NanoCleanSQ that kills virtually all viruses and bacteria on high-touch surfaces such as doorknobs and handrails. “We always knew that our SmogStop pollution removal technology had the ability to kill bacteria and viruses, but it was not optimized for this purpose,” says Scott Shayko, CEO of EnvisionSQ. “We specifically reformulated SmogStop to help society combat the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Testing people for infection or immunity is another strategy for tamping disease spread. Several diagnostic tools for detecting the coronavirus have been developed from DNA-based species surveillance technology pioneered in U of G’s Centre for Biodiversity Genomics (CBG). Normally, that technology based on DNA barcoding allows for accurate identification of species of organisms and is used, for example, in detecting food fraud and monitoring cross-border traffic in endangered animals. By focusing on a single viral gene, CBG scientists aim to provide a rapid $1 COVID-19 test for screening numerous samples at once.

Another mobile test kit based on CBG innovation and produced by Guelph-based Precision Biomonitoring is being used in remote and rural communities, such as northern Indigenous communities. Company co-founder and integrative biology professor Robert Hanner developed environmental DNA technology for detecting aquatic organisms from trace amounts of genetic material contained in water samples. He is now exploring other uses for monitoring COVID-19 in municipal wastewater and foods. Mario Thomas, CEO of Precision Biomonitoring, says that when a board member asked whether the company could adapt its molecular tools for a COVID-19 test, “we thought for about 10 seconds and decided to pivot and expand to the health-care market.”

Such screening will be particularly invaluable as Canada moves to reopen its economy, including restarting businesses and schools while avoiding a resurgence of infections. Balancing population health with economic well-being means relying largely on models of disease spread and containment, including work by U of G experts in several disciplines. Helping to find that balance, including determining how to relax or tighten physical distancing measures, is the work of population medicine professor Amy Greer, holder of the Canada Research Chair in Population Disease Modelling and a member of a COVID-19 modelling advisory group of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

As part of a research team led by University of Toronto epidemiologists and supported by COVID-19 funding from CIHR, she found that so-called dynamic physical distancing – dialling distancing measures up and down – could help reduce disease spread while not overwhelming intensive-care units. Speaking about the team’s results this spring, Greer says, “Easing off control measures periodically risks disease resurgence. But allowing people and the economy to ‘come up for air’ over the next few months offers a more effective and palatable strategy for fighting COVID-19 while ensuring that ICUs can handle infected cases.” Graduate students and researchers in her department have worked with U of T colleagues on an online dashboard tracking the spread of the coronavirus across Canada. Says Greer, “It’s nice to do work that you feel is important and useful.”

Mathematical modelling of strategies for reopening schools, businesses and workplaces has also been a focus of Madhur Anand, a professor in the School of Environmental Sciences and director of U of G’s Guelph Institute for Environmental Research, applied methods used to model climate change mitigation to modelling mitigation strategies for COVID-19, including reopening of the economy. Her study this spring with U of G and University of Waterloo colleagues compared a strategy of local reopening (and reclosing as needed) with a province-wide strategy. They found that a tailored approach of local reopening results in far fewer days of closure with only slightly more coronavirus disease. In the School of Engineering, Profs. Ed McBean and Andrew Gadsden have received federal funding to apply artificial intelligence in predicting COVID-19 impacts on Canada’s health-care system as provinces restart their economies. From gauging needs for ventilators to predicting any likely new wave of coronavirus cases, the project aims to help decision-makers in government, business and health care to plan next steps.

Looking beyond the COVID-19 curve, management professor Felix Arndt says businesses need to consider online alternatives necessitated by the coronavirus. Embracing organizational and technological change may help companies weather this pandemic and other so-called “black swan events,” says Arndt, who holds the John F. Wood Chair in Entrepreneurship in U of G’s Gordon S. Lang School of Business and Economics. Other experts in the school who commented this spring on the commercial and business effects of the coronavirus included Prof. Marion Joppe, School of Hospitality, Food and Tourism Management, discussing impacts on travel and tourism, and human resources expert Nita Chhinzer in the Department of Management on back-to-work policies and challenges. Prof. Norm O’Reilly, director of Lang’s International Institute for Sport Business and Leadership, was appointed to three subcommittees launched by the federal Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture to advise on economic impacts of the pandemic and its aftermath. Former dean Julia Christensen Hughes and Prof. Melanie Lang, executive director of the John F. Wood Centre for Business and Student Enterprise, were invited to participate in the Mayor’s Task Force on Economic Recovery for the City of Guelph.

One crucial aspect of the pandemic for businesses, consumers and Canada’s food university has been its impact on food supply and security in this country and worldwide. Those topics have attracted repeated media calls to several U of G faculty members, including Mike von Massow, Department of Food, Agricultural and Rural Economics (FARE); food scientist Jeff Farber, former director of U of G’s Canadian Research Institute for Food Safety; and geography professor Evan Fraser, director of the University’s Arrell Food Institute (AFI).

Aiming to help spark a national dialogue on food policy recommendations and future research, Fraser will co-chair a new national project launched by the AFI and the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute (CAPI). Conclusions and recommendations from the “Growing Stronger” project will be discussed at the 2020 Arrell Food Summit and at a CAPI forum next year. “In the post-COVID-19 world, seeking answers to the key question of how to build a resilient Canadian agri-food system will become more urgent than ever, as this crisis brings to light where we successfully adapted as well as revealing hidden vulnerabilities in that system,” says Fraser.

This spring, several FARE faculty members contributed to a special edition of the Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics on the pandemic’s impacts on commodities, the food industry, and supply chain and labour issues. Co-editor Prof. Alan Ker, holder of the Ontario Agricultural Research Chair in Agricultural Risk and Policy and director of the Institute for the Advanced Study of Food and Agricultural Policy, says, “There have been some supply glitches, and you could argue that this been a natural test for the country’s food system, but the system has proved remarkably resilient to date.” He says the journal’s contributors aimed to help inform public policy during an uncertain time.

This spring, several FARE faculty members contributed to a special edition of the Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics on the pandemic’s impacts on commodities, the food industry, and supply chain and labour issues. Co-editor Prof. Alan Ker, holder of the Ontario Agricultural Research Chair in Agricultural Risk and Policy and director of the Institute for the Advanced Study of Food and Agricultural Policy, says, “There have been some supply glitches, and you could argue that this been a natural test for the country’s food system, but the system has proved remarkably resilient to date.” He says the journal’s contributors aimed to help inform public policy during an uncertain time.

That’s also the goal of a new project involving a U of G researcher intended to incorporate the public voice in COVID-19-related government policy. Psychology professor Kieran O’Doherty is working with researchers from the University of British Columbia on ensuring that decision-makers incorporate public input on policies including contact-tracing apps and physical distancing measures. “The public deliberation process is important because rather than seek public opinion through surveys, which tend to be unreflective, deliberation allows participants to work together to gain knowledge about an issue and take diverse perspectives into account when making recommendations to policy-makers,” says O’Doherty. “It is our hope that it can help shape COVID-19 policy going forward.”

On another front, sharing information and maintaining relations among scientists, governments and the public will be crucial to ensuring acceptance to a COVID-19 vaccine, says philosophy professor Maya Goldenberg. A specialist in the philosophy of science and medicine, she says vaccine hesitancy often reflects public distrust of scientific institutions and governance. She says this country currently has a window to educate the public on how vaccines are developed, tested and approved. “At the moment, Canada is enjoying very high trust in government response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The prospect of a COVID-19 vaccine becoming available to Canadians should be part of the government communications right now, so that the public can begin considering it.”

U of G experts also weighed in with ideas for individuals and families to weather the lockdown and associated measures such as physical distancing. Prof. Jess Haines, Department of Family Relations and Applied Nutrition and co-director of the Guelph Family Health Study, advised families to stick to useful routines for bedtime, exercise and healthy eating while balancing screen time with screen-free family time. A virtual well-being project this spring based in the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) gained fans across Canada and worldwide through social media channels; the project promoted weekly ideas for stress relief based on eight domains of well-being, including emotional, intellectual, physical and spiritual aspects. “We’re helping people to see that, yes, things are different and hard right now with COVID-19, but there are still ways to work around it and engage with well-being activities,” says population medicine professor Andria Jones-Bitton, who early this year became OVC’s inaugural director of well-being.

Family well-being extends to pets, says pathobiology professor Scott Weese, chief of infection control at OVC. Quoted widely this spring about pets and COVID-19, he’s studying the risks posed to animals by coronavirus in humans. “We’re trying to understand how often human-to-animal spread happens,” says Weese, who is working with pathobiology professor Dorothee Bienzle. “We already know it can happen; we’ve seen it in various instances. Now we’re trying to find how common it is.” He’s also part of a larger research project looking at global management of COVID-19 using a “one health” approach that brings together animal and human disease experts. Led by University of Ottawa epidemiologists, the $500,000 project will lead to recommendations about improving responses to infectious disease.

Such a one health approach will be critical in helping to predict and prevent future outbreaks, says David Waltner-Toews, emeritus professor in population medicine. That’s the message in his book On Pandemics: Deadly Diseases from Bubonic Plague to Coronavirus, published this spring. He says experts from public health to ecology to business need to collaborate in monitoring potential outbreaks. He also calls for a rethink of ecological, economic and political factors that help account for zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19 that jump from animals to humans. Climate change impacts, food production practices, growing world trade and travel, and loss of biodiversity all bring humans, animals and their associated microbes into closer contact, writes Waltner-Toews. Referring to worldwide lockdowns this year, he says, “We have an opportunity to reorganize and renew ecological and social relationships that we haven’t had for decades, probably since the 1918 influenza pandemic.”

Such a one health approach will be critical in helping to predict and prevent future outbreaks, says David Waltner-Toews, emeritus professor in population medicine. That’s the message in his book On Pandemics: Deadly Diseases from Bubonic Plague to Coronavirus, published this spring. He says experts from public health to ecology to business need to collaborate in monitoring potential outbreaks. He also calls for a rethink of ecological, economic and political factors that help account for zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19 that jump from animals to humans. Climate change impacts, food production practices, growing world trade and travel, and loss of biodiversity all bring humans, animals and their associated microbes into closer contact, writes Waltner-Toews. Referring to worldwide lockdowns this year, he says, “We have an opportunity to reorganize and renew ecological and social relationships that we haven’t had for decades, probably since the 1918 influenza pandemic.”

That Janus-like perspective was mirrored in Shelter/Place: A Virtual Wunderkammer, a project involving U of G students in an introductory museology course taught this past winter by Shauna McCabe, director of the Art Gallery of Guelph. Arriving mid-course, the pandemic altered their planned pop-up museum of found and personal artifacts. Instead, they assembled a virtual display that focused on negotiating physical objects and spaces under restricted access to both. History major Haiden Vollebregt said that, under pandemic isolation from loved ones, a mug given to her by her mother has become a reminder of human connection and community compassion.

“The students have used this unique moment as an opportunity to think about how our current situation reframes the past and prompts us to reimagine the present and the future,” says McCabe. Words to live by as U of G, and the whole world, peers into life beyond the COVID-19 curve.