Amid fake news and viral misinformation about everything from U.S. election results to COVID-19 guidelines, what hope is there for rational thought and science to prevail?

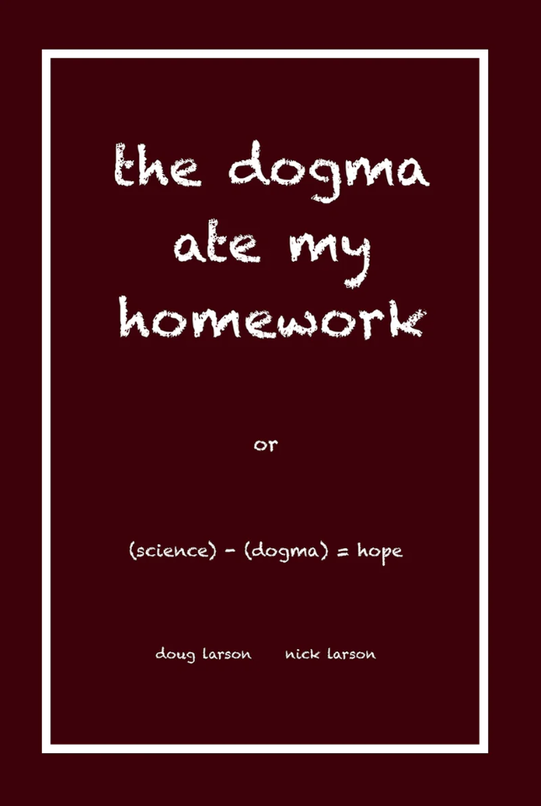

Turning the question around is the solution in a new book by Dr. Doug Larson, emeritus professor in the Department of Integrative Biology in the University of Guelph’s College of Biological Science. “Hope is achieved by allowing science to destroy dogma,” says Larson in the cover blurb to The Dogma Ate My Homework.

Co-authored by his son Nick, the new book is published by Volumes Publishing in Kitchener, Ont.

The father-and-son writing team urges readers to harness science to confront unquestioned beliefs that prevent people and societies from realizing their potential. That idea is embodied in their volume’s subtitle, framed – suitably, for an ecologist and his engineer son – as a home-made equation: (Science) – (Dogma) = Hope.

Dogma wielded by authorities is a corruptive and paralyzing influence, said Larson during an interview this fall on campus. But that’s only part of the problem.

Perhaps the only thing more destructive than manipulative powers, he said, is a human tendency to accept beliefs without challenge. Why would we do that?

Call it a case of going along to get along – and an aversion to confrontation.

Someone says something and no one questions it: That’s dogma

“We’d rather believe things to be true than for them to be true. It makes things more palatable,” said Larson, who taught and studied at U of G from 1975 until retirement in 2009.

“It’s dogma if someone says something and no one questions it.”

For instance, he said, there’s an increasingly widespread and angsty sentiment that humanity is collectively decimating our planet through climate change and other factors.

Human activities are undoubtedly affecting climate, said Larson.

He points to his early studies of arctic lichens, which occurred well before his headline-generating discovery in the 1990s that ancient dwarf cedars grow on the Niagara Escarpment.

For those studies, he used an instrument calibrated to ambient atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration of 345 parts per million. Today’s global CO2 average is 420 ppm, a nearly 25-per-cent increase in almost half a century.

But, said Larson, it’s not true that “we are destroying the planet.” That dogmatic notion suggests that we pose a collective existential threat to Earth’s ecosystems.

Climate change may play havoc with investments or winter weather or coastal homes and livelihoods. But it doesn’t destroy Earth’s living systems that predate humanity and that will likely outlast us.

“Climate change and other risks destroy all the things we like,” said Larson. “The phrase, ‘We are destroying the planet’ really says that ‘we like the planet just the way it is.’”

Rather than simply endorse blanket statements that effectively prompt handwringing but little action, he said, we need to plan for and adapt to climate change – human-made and natural. Similarly, he said, dogma and propaganda about biodiversity loss, infectious disease and the threat of nuclear war wrap the issues in a “wall of fear.”

Or, to use another metaphor, Larson said, “We swim inside a big ocean of misrepresentation.”

For these and other concerns, he said, the best strategy is to focus on what we can change.

Looking past ‘dogma’ of taxes and centralization

In its signal example, The Dogma Ate My Homework proposes that we stop looking to centralized government to solve problems such as climate change or biodiversity loss.

Centralized government rests on the dogma of taxation as the primary source of public infrastructure, Larson said.

Yet governments are caught between relying on tax money to fund infrastructure and their own reluctance to alienate voters with tax increases. Coupled with public ownership of everything from roads to bridges to sewers, what results is a kind of “tragedy of the commons” with crumbling or outdated infrastructure that no one wants to pay to repair.

Instead, Larson calls for more private investment in infrastructure, such as funding by investors in late nineteenth-century Guelph that paid for construction of an urban railroad system in the city.

“Governments now own our infrastructure,” he said. Far from the dogma of public ownership and reliance on taxation, Larson added, “Infrastructure is a commodity that people can invest in.”

The book also discusses why and how dogma works, points to hope as an evolutionary process and outlines how the scientific method helps to counter dogma.

Larson draws on ideas from such public intellectuals as the American biophysicist Harold Morowitz, who studied thermodynamics and living systems; the American astronomer Frank Drake; the Swedish physician and academic Hans Rosling; and Jacob Bronowski, a mathematician and philosopher who explored humanism and science in a 1973 book and television documentary series called The Ascent of Man.

As a U of G professor, Larson said, he spent decades teaching students not just about ecology but about the power of dogma and its ill effects. A longtime musician, he wrote and recorded ideas on dogma and critical thinking in a 2015 album called Things That Need to Be Said.

Contact:

Doug Larson

dwlarson@uoguelph.ca