The Research Process

The following pages were created to allow hospitality and tourism managers to familiarize themselves with some of the basic quantitative and qualitative research techniques, concepts and terminology. The objective is to provide this information in an easily accessible format and non-technical language, and link it to references for more in-depth information and other research sites. This undertaking was made possible by the generous support of the Ontario Hostelry Institute, AMEX Canada, and Ryerson University.

The research process involves six distinct phases, although they are not always completely linear, since research is iterative (earlier phases influence later ones, while later ones can influence the earlier phases). Perhaps one of the most important characteristics of a good researcher is the unwillingness to take shortcuts, to rush through the research. It is important to keep an open mind to recognize changes that must be accomodated to ensure the reliability and validity of the research.

1. Problem Definition

Although research reports state the objectives or purpose of the research early on, this is not always the starting point. Often, considerable analysis of historical data or secondary information has been undertaken to help define in very clear and precise terms what is the problem or opportunity. Apparently, Albert Einstein went so far as to say that "the formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution"! Sometimes, exploratory research is required to help in the formulation of the research problem.

After an introduction which describes the broader context within which the research should be situated, it is important to state the objectives or purpose pursued by the research itself. Often, this is a fairly broad or general statement as well. For instance, in the paper "Not in my backyard: Toronto Resident Attitudes toward Permanent Charity Gaming Clubs", the purpose of the research is given as: "The following study is an attempt to provide a more meaningful and defensible measure of public opinion". This is a fairly vague statement and should have been followed up with a much more precise research question (in question format) or problem statement (a re-wording of the research question into a statement format). For example "What is the attitude of Toronto residents toward permanent charity gaming clubs?"; (research question) or "This study is designed to determine the attitude of Toronto residents toward permanent charity gaming clubs"; (problem statement).

Indeed, the research question could have been broken down further, into subproblems. For instance, "Are there differences in attitude based on age, education and gender?"; or "What are the primary reasons for residents approving or disapproving of permanent charity gaming clubs?"; These subproblems form the nucleus of the research itself and must be directly addressed by the research instrument.

At this point in time it is important to inform the reader about the breadth or scope of the study, in our particular case this includes Toronto residents (the term "Toronto" should probably be defined to ensure a common understanding as to the geographic boundaries) and questions pertaining to permanent casinos and VLTs (but not bingo halls or lotteries, for instance). This scope might be considered to be too broad in nature, and so the researcher can impose limitations or restrictions on the study that make it more doable. As an example, this study was limited to respondents aged 19 or older. Other limitations may have to be imposed on the study due to cost or time constraints or accessibility to respondents. This type of limitation should NOT be confused with methodological limitations, which are addressed as part of the methodology of the study.

All research is based on a set of assumptions or factors that are presumed to be true and valid. For instance, it is generally assumed that respondents will reply honestly and accurately as far as they are able to do so. By stating these assumptions up front, the researcher reduces potential criticism of the research, but without them, the research itself would not be possible. If you thought that respondents would lie, why would you bother doing the research?

In formal research, the researcher will provide an educated guess regarding the outcome of the study, called hypothesis (note that the plural form is hypotheses!). The "educated guess" comes from the related literature. You can also think of hypotheses as the expected answer to the research question and each of the subproblems. The research will test the hypotheses, proving them to be either valid or correct, or invalid/incorrect. Sometimes, researcher will also state that a hypothesis tested positive (valid) or negative (incorrect). It does not matter whether you correctly predict the outcome of the research or not, since rejecting a hypothesis does not mean that the research itself is poor, but rather that your research has results that are different from what the related literature led you to believe should have been expected.

In the case of industry research, once the manager has defined the problem for which s/he needs a solution, and has determined that the information required cannot be obtained using internal resources, an outside supplier will likely be contracted based on a Request for Proposal.

The Request for Proposal (RFP)

The request for proposal (RFP) is part of a formal process of competitively tendering and hiring a research supplier. If the process is undertaken by a public sector organization or large corporation, the process can be extremely strict with set rules regarding communication between client and potential suppliers, the exact time when the proposal must be submitted, the number of copies to be provided, etc. Proposals that required thousands of hours of preparation have been refused for being one minute late (see this article)!

The RFP usually sets out the objectives or client’s information requirements and requests that the proposal submitted by the potential supplier include:

- A detailed research methodology with justification for the approach or approaches proposed;

- Phasing or realistic timelines for carrying out the research;

- A detailed quotation by phase or task as well as per diem rates and time spent for each researcher participating in the execution of the work;

- The qualifications of each participating researcher and a summary of other projects each person has been involved in to demonstrate past experience and expertise

The client should provide the potential suppliers with the criteria for selection and the relative weight assigned to each one, to assist suppliers in understanding where trade-offs might need to be made between available budget and importance. These criteria also allow the supplier to ensure that all areas deemed important by the client have been addressed as part of the proposal.

At times, clients ask a short-listed number of suppliers to present their proposed methodology during an interview, which allows for probing by the client but also discussion as to the advantages and disadvantages associated with the research design that is proposed.

2. Literature Review

Knowledge is cumulative: every piece of research will contribute another piece to it. That is why it is important to commence all research with a review of the related literature or research, and to determine whether any data sources exist already that can be brought to bear on the problem at hand. This is also referred to as secondary research. Just as each study relies on earlier work, it will provide a basis for future work by other researchers.

The literature review should provide the reader with an explanation of the theoretical rationale of the problem being studied as well as what research has already been done and how the findings relate to the problem at hand. In the paper "Not in my backyard: Toronto Resident Attitudes toward Permanent Charity Gaming Clubs", Classen presented the context of the current gaming situation, the Canadian and local gaming scene including theories as the acceptance of gaming and its future, as well as studies regarding the economic and social issues relating to gaming and how these affect residents’ opinions. It is most helpful to divide the literature into sub-topics for ease of reading.

The quality of the literature being reviewed must be carefully assessed. Not all published information is the result of good research design, or can be substantiated. Indeed, a critical assessment as to the appropriateness of the methodology employed can be part of the literature review, as Classen did with the Bradgate Study on Public Opinion.

This type of secondary research is also extremely helpful in exploratory research. It is an economical and often easily accessible source of background information that can shed light on the real scope of the problem or help familiarize the researcher with the situation and the concepts that require further study.

3. Selection of Research Design, Subjects and Data Collection Techniques

Once the problem has been carefully defined, the researcher needs to establish the plan that will outline the investigation to be carried out. The research design indicates the steps that will be taken and in what sequence they occur.

There are two main types of research design:

- Exploratory research

- Conclusive research itself subdivided into

Each of these types of research design can rely on one or more data collection techniques:

- Observation technique

- Direct communication with subjects, e.g. survey technique, interview or projective methods

- Secondary research, which essentially means reviewing literature and data sources, collected for some other purpose than the study at hand.

Irrespective of the data collection technique used, it is critical that the researcher analyze it for its validity and reliability.

Another critical consideration in determining a study’s methodology is selection of subjects. If the researcher decides to study all elements within a population, s/he is in fact conducting a census. Although this may be ideal, it may not be very practical and can be far too costly. The alternative is to select a sample from the population. If chosen correctly, it is considered to be representative of the population. In this case, we are dealing with one of the probability sampling techniques. If the sample is not representative, then one of the non-probability sampling techniques was employed.

When research is written up as a part of a newspaper article, there should always be an indication as to the methodology employed, as is the case with the attached article.

Exploratory Research

As the term suggests, exploratory research is often conducted because a problem has not been clearly defined as yet, or its real scope is as yet unclear. It allows the researcher to familiarize him/herself with the problem or concept to be studied, and perhaps generate hypotheses to be tested. It is the initial research, before more conclusive research is undertaken. Exploratory research helps determine the best research design, data collection method and selection of subjects, and sometimes it even concludes that the problem does not exist!

Another common reason for conducting exploratory research is to test concepts before they are put in the marketplace, always a very costly endeavour. In concept testing, consumers are provided either with a written concept or a prototype for a new, revised or repositioned product, service or strategy.

Exploratory research can be quite informal, relying on secondary research such as reviewing available literature and/or data, or qualitative approaches such as informal discussions with consumers, employees, management or competitors, and more formal approaches through in-depth interviews, focus groups, projective methods, case studies or pilot studies.

The results of exploratory research are not usually useful for decision-making by themselves, but they can provide significant insight into a given situation. Although the results of qualitative research can give some indication as to the "why", "how" and "when" something occurs, it cannot tell us "how often" or "how many". In other words, the results can neither be generalized; they are not representative of the whole population being studied.

Conclusive Research

As the term suggests, conclusive research is meant to provide information that is useful in reaching conclusions or decision-making. It tends to be quantitative in nature, that is to say in the form of numbers that can be quantified and summarized. It relies on both secondary data, particularly existing databases that are reanalyzed to shed light on a different problem than the original one for which they were constituted, and primary research, or data specifically gathered for the current study.

The purpose of conclusive research is to provide a reliable or representative picture of the population through the use of a valid research instrument. In the case of formal research, it will also test hypothesis.

Conclusive research can be sub-divided into two major categories:

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research or statistical research provides data about the population or universe being studied. But it can only describe the "who, what, when, where and how" of a situation, not what caused it. Therefore, descriptive research is used when the objective is to provide a systematic description that is as factual and accurate as possible. It provides the number of times something occurs, or frequency, lends itself to statistical calculations such as determining the average number of occurences or central tendencies.

One of its major limitations is that it cannot help determine what causes a specific behaviour, motivation or occurrence. In other words, it cannot establish a causal research relationship between variables.

The two most commonly types of descriptive research designs are

- Observation and

- Surveys

Causal Research

If the objective is to determine which variable might be causing a certain behaviour, i.e. whether there is a cause and effect relationship between variables, causal research must be undertaken. In order to determine causality, it is important to hold the variable that is assumed to cause the change in the other variable(s) constant and then measure the changes in the other variable(s). This type of research is very complex and the researcher can never be completely certain that there are not other factors influencing the causal relationship, especially when dealing with people’s attitudes and motivations. There are often much deeper psychological considerations, that even the respondent may not be aware of.

There are two research methods for exploring the cause and effect relationship between variables:

Primary Research

In primary research, data is collected specifically for the study at hand. It can be obtained either by the investigator observing the subject or phenomenon being studied, or communicating directly or indirectly with the subject. Direct communication techniques include such qualitative research techniques as in-depth interview, focus group and projective techniques, and quantitative research techniques such as telephone, self-administered and interview surveys.

Observation

Observation is a primary method of collecting data by human, mechanical, electrical or electronic means. The researcher may or may not have direct contact or communication with the people whose behaviour is being recorded. Observation techniques can be part of qualitative research as well as quantitative research techniques. There are six different ways of classifying observation methods:

- participant and nonparticipant observation, depending on whether the researcher chooses to be part of the situation s/he is studying (e.g. studying social interaction of tour groups by being a tour participant would be participant observation)

- obtrusive and unobtrusive (or physical trace) observation, depending on whether the subjects being studied can detect the observation (e.g. hidden microphones or cameras observing behaviour and doing garbage audits to determine consumption are examples of unobtrusive observation)

- observation in natural or contrived settings, whereby the behaviour is observed (usually unobtrusively) when and where it is occurring, while in the contrived setting the situation is recreated to speed up the behaviour

- disguised and non-disguised observation, depending on whether the subjects being observed are aware that they are being studied or not. In disguised observation, the researcher may pretend to be someone else, e.g. "just" another tourist participating in the tour group, as opposed to the other tour group members being aware that s/he is a researcher.

- Structured and unstructured observation, which refers to guidelines or a checklist being used for the aspects of the behaviour that are to be recorded; for instance, noting who starts the introductory conversation between two tour group members and what specific words are used by way of introduction.

- Direct and indirect observation, depending on whether the behaviour is being observed as it occurs or after the fact, as in the case of TV viewing, for instance, where choice of program and channel flicking can all be recorded for later analysis.

The data being collected can concern an event or other occurrence rather than people. Although usually thought of as the observation of nonverbal behaviour, this is not necessarily true since comments and/or the exchange between people can also be recorded and would be considered part of this technique, as long as the investigator does not control or in some way manipulate what is being said. For instance, staging a typical sales encounter and recording the responses and reactions by the salesperson would qualify as observation technique.

One distinct advantage of the observation technique is that it records actual behaviour, not what people say they said/did or believe they will say/do. Indeed, sometimes their actual recorded behaviour can be compared to their statements, to check for the validity of their responses. Especially when dealing with behaviour that might be subject to certain social pressure (for example, people deem themselves to be tolerant when their actual behaviour may be much less so) or conditioned responses (for example, people say they value nutrition, but will pick foods they know to be fatty or sweet), the observation technique can provide greater insights than an actual survey technique.

On the other hand, the observation technique does not provide us with any insights into what the person may be thinking or what might motivate a given behaviour/comment. This type of information can only be obtained by asking people directly or indirectly.

When people are being observed, whether they are aware of it or not, ethical issues arise that must be considered by the researcher. Particularly with advances in technology, cameras and microphones have made it possible to gather a significant amount of information about verbal and non-verbal behaviour of customers as well as employees that might easily be considered to be an invasion of privacy or abusive, particularly if the subject is unaware of being observed, yet the information is used to make decisions that impact him/her.

Direct Communication

There are many different ways for the investigator to collect data from subjects by communicating directly with them either in person, through others or through a document, such as a questionnaire. Direct communication is used in both qualitative and quantitative research. Each has a number of different techniques:

1. Qualitative research techniques

2. Quantitative research techniques

Qualitative Research Techniques

Although qualitative research can be used as part of formal or conclusive research, it is most commonly encountered when conducting exploratory research. Qualitative research techniques are part of primary research.

Qualitative research differs from quantitative research in the following ways:

- The data is usually gathered using less structured research instruments

- The findings are more in-depth since they make greater use of open-ended questions

- The results provide much more detail on behaviour, attitudes and motivation

- The research is more intensive and more flexible, allowing the researcher to probe since s/he has greater latitude to do so

- The results are based on smaller sample sizes and are often not representative of the population,

- The research can usually not be replicated or repeated, given it low reliability; and

- The analysis of the results is much more subjective.

Because of the nature of the interaction with respondents, the training and level of expertise required by the person engaging in the direct communication with the respondents must be quite high.

The most common qualitative research techniques include:

- In-depth interview

- Focus group

- Projective methods

- Case study

- Pilot study

The Experience Survey

Any time a researcher or decision-maker needs to gain greater insight into a particular problem, he or she is likely to question knowledgeable individuals about it. This is usually done through an informal, free-flowing conversation with anyone who is believed to be able to shed light on the question both within the organization and outside it. Such an approach is referred to as an experience survey. It is only meant to help formulate the problem and clarify concepts, not develop conclusive evidence.

People seen as providing the insight necessary are not only found in the top ranks of an organization or amongst its "professional" staff, but can also involve front line employees. Who else, for instance, is better placed to comment on recurring complaints from guests? In an experience survey, respondents are not selected randomly nor are they representative of the organization or department within which they work. Rather, they are knowledgeable, articulate and thoughtful individuals.

Related Readings (Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

Case Study

When it is deemed desirable to learn from the experience of others, researchers often resort to the case study. In this comprehensive description and analysis of one or a few situations that are similar to the one being studied, the emphasis is on an entire organization with great attention paid to detail in order to understand and document the relationships among circumstances, events, individuals, processes, and decisions made.

In order to obtain the information required, it is usually necessary to conduct a depth interview with key individuals in the organization as well as consulting internal documents and records or searching press reports. Observation of actual meetings, sales calls or trips, negotiations, etc. can also prove insightful, since "actions speak louder than words", even when it comes to understanding how decisions are made in an organization or why some organizations are more successful than others.

However, caution must be exercised in transferring lessons to other situations: there is no "formula" that can be applied, but rather a context that must be understood and interaction among individuals that must be appreciated. Individual personalities, their vision and drive contribute as much if not more to the success of an organization than processes.

Related Readings (link to Library. Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

Pilot Study

When data is collected from a limited number of subjects selected from the population targetted by the research project, we refer to it as a pilot study. A pilot study can also take the form of a trial run. For instance, an advertising campaign is tested in a specific market before it goes nation-wide, to study the response by potential consumers.

In a pilot study, the rigorous standards used to obtain precise, quantitative estimates from large, representative samples are often relaxed, since the objective is to gain insight into how subjects will respond prior to administering the full survey instrument. Although a pilot study constitutes primary research, it tends to be used in the context of a qualitative analysis.

There are four major qualitative research techniques that can be used as part of a pilot study. These are

- Depth interview

- Focus group (or group depth interview)

- Panel

- Projective technique

Related Readings (Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

In-Depth Interview

When it is important to explore a subject in detail or probe for latent attitudes and feelings, the in-depth interview may be the appropriate technique to use. Depth interviews are usually conducted in person, although telephone depth interviewing is slowly gaining greater acceptance.

With the approval of the respondent, the interview is audio taped, and may even be video-taped, in order to facilitate record keeping. Although it is a good idea to prepare an interview guide ahead of time to be sure to cover all aspects of the topic, the interviewer has significant freedom to encourage the interview to elaborate or explain answers. It is even possible to digress from the topic outline, if it is thought to be fruitful.

Interviewers must be very experienced or skilled, since it is critical that s/he and the respondent establish some kind of rapport, and that s/he can adapt quickly to the personality and mood of the person being interviewed. This will elicit more truthful answers. In order to receive full cooperation from the respondent, the interviewer must be knowledgeable about the topic, and able to relate to the respondent on his/her own terms, using the vocabulary normally used within the sector being studied. But the interviewer must also know when it is necessary to probe deeper, get the interviewee to elaborate, or broaden the topic of discussion.

Since an interview can last anywhere from 20 to 120 minutes, it is possible to obtain a very detailed picture about the issues being researched. Even without considering the potential from interviewer bias, analyzing the information obtained requires great skill and may be quite subjective. Quantifying and extrapolating the information may also prove to be difficult.

Related Readings (Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

Focus Group

In the applied social sciences, focus group discussions or group depth interviews are among the most widely used research tool. A focus group takes advantage of the interaction between a small group of people. Participants will respond to and build on what others in the group have said. It is believed that this synergistic approach generates more insightful information, and encourages discussion participants to give more candid answers. Focus groups are further characterized by the presence of a moderator and the use of a discussion guide. The moderator should stimulate discussion among group members rather than interview individual members, that is to say every participant should be encouraged to express his/her views on each topic as well as respond to the views expressed by the other participants. In order to put focus group participants at ease, the moderator will often start out by assuring everyone that there are no right or wrong answers, and that his/her feelings cannot be hurt by any views that are expressed since s/he does not work for the organization for whom the research is being conducted.

Although the moderator's role is relatively passive, it is critical in keeping the discussion relevant. Some participants will try to dominate the discussion or talk about aspects that are of little interest to the research at hand. The type of data that needs to be obtained from the participants will determine the extent to which the session needs to be structured and therefore just how directive the moderator must be.

Although focus group sessions can be held in many different settings, and have been known to be conducted via conference call, they are most often conducted in special facilities that permit audio recording and/or video taping, and are equipped with a one-way mirror. This observation of research process as it happens can be invaluable when trying to interpret the results. The many disparate views that are expressed in the course of the 1 to 2 hour discussion make it at times difficult to capture all observations on each topic. Rather than simply summarizing comments, possible avenues for further research or hypotheses for testing should be brought out.

Focus groups are normally made up of anywhere between 6 and 12 people with common characteristics. These must be in relation to what is being studied, and can consist of demographic characteristics as well as a certain knowledge base or familiarity with a given topic. For instance, when studying perceptions about a certain destination, it may be important to have a group that has visited it before, while another group would be composed of non-visitors. It must, however, be recognized that focus group discussions will only attract a certain type of participant, for the most part extroverts. (Read the set-up for a focus group on the perception and image of a destination in Southwestern Ontario.)

It is common practice to provide a monetary incentive to focus group participants. Depending on the length of the discussion and the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants being recruited, this can range anywhere from $30 to $100 per hour and more for professionals or other high income categories. Usually several focus groups are required to provide the complete diversity of views, and thus this is a fairly expensive option among the research techniques.

This incentive makes it easier to recruit participants, but can also lead to professional respondents. These are people who participate in too many focus groups, and thus learn to anticipate the flow of the discussion. Some researchers believe that these types of respondents no longer represent the population. See the following letter "Vision is blurred..." and response "Focus groups gain key insights..." that appeared in the Toronto Star, for instance.

For further information on focus groups, check out Smartpoint Research Focus Group and also see their links for additional background. You can even sign up to participate in a focus group yourself!

Related Readings (Stewart, D.W. & Shamdasani, P.N. (1990), Focus Groups: Theorgy and Practice. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

THE TORONTO STAR Saturday, August 14, 1999 A27

THE TORONTO STAR Saturday, August 14, 1999 A27

Focus groups gain key insights into needs

Re Vision is blurred (Opinion page Aug. 5).

The opinion piece about focus group participation written by Michael Dojc contains many blanket statements based on supposition, with little to link it to quantifiable facts.

Dojc seems to attribute an apathy and incompetence to the recruiters who so willingly (in his view) allow a self-admitted liar such as himself to gain admittance to these groups.

He also seems to think that the recruiting industry is somehow at fault for not finding him out.

As is the case with many activities within this 3ociety, market researchers

have to rely to some degree on the inherent honesty and goodwill of everyday people.

Focus groups provide a unique and Important medium for marketers to gain key insights into target consumers attitudes, needs and wants in a dialogue that allows for in-depth probing.

And, in my observation, not only do Many focus group participants enjoy the opportunity to provide legitimate feedback about a product or service, most understand that their reactions, thoughts, and feelings may have a substantive impact on marketing activities, and as such they do not actively misrepresent themselves.

Of course, there are always a few "bad apples" out to milk the system for whatever they can get.

To weed out these people, Central Files, a centralized database of focus group participants, exists to maintain control over the frequency of respondent attendance, and to exclude undesirable respondents (defined as those who have been determined to have lied during screening, been overly disruptive during a group session, or those classified as professional respondents because they have attended many more groups than normal as a way to make extra money).

The ability of the system to function

effectively is directly related to the number of firms who participate.

The Professional Marketing Research Society, of which I am a member, strongly endorses that all researchers buy recruiting services from those firms who submit names to Central Files, to minimize the chance that fake respondents such as Dojc slip through.

Dojc's description of his interaction with focus group recruiters serves more to reveal his own moral inadequacies (Lying and cheating to make a few bucks) than to expose systemic problems in the research recruitment sector.

CAMILLA LEONARD

THE TORONTO STAR Saturday, August 5, 1999 A21

|

THE TORONTO STAR Saturday, August 5, 1999 A21 |

|||

|

Vision is blurred at many focus groups |

|||

|

BY MICHAEL DOJC Many market, research groups are experiencing tunnel vision when it experiencing tunnel vision when it comes to focus group testing. By dipping and double dipping and triple dipping into the same pool of people again and again, focus groups are really working with a fuzzy lens. I started attending focus groups when I was 16 years old and I always relished the experience of not only trying out a new product, but being paid for it as well. Though it didn't take long for me to rush through the surveys, get my cash and run. Since then, I have been repeatedly called, approximately twice a month, by the various groups in the Toronto area and even more times since I turned 19. But now the novelty has worn off and I am beginning to realize the sheer inconsequence of the groups. I am not the only disenchanted frequent focus group attendee at these gatherings. It did not take long to notice that it is the same people who go every time. We all know the drill so well that we are never refused entry by the faceless telephone operators who screen candidates. |

I came up with this simple formula that has never failed me yet. The first thing you have to realize is that the person on the other end of the phone does not care about you, and while they may not believe everything you say, they will diligently write it down as if it were the gospel. The following is an example of the typical screening process: "Hi, this is Casey from X recruiting, would you be interested in participating in a focus group? It pays $30 for 45 minutes." The answer to this question is an assured "yes" or "sure," depending on your personal preference both will do quite fine. "First we have to see if you qualify. Have you done a focus group in the last three months?" The answer is "no." Even if you have attended one, they will never check their records and even if the same person called you the last time, it is highly unlikely they will remember, considering that they make hundreds of calls every day. "Do you or any of your immediate family members work in advertising, television, journalism or media?" |

Again the answer is "no" and the same aforementioned rules apply. "Which of the following have you purchased in the last week?" The answer to any question of this type is always an affirmative "yes." Never take a chance. The one negative you give could be the qualifying question. It has happened to me-on numerous occasions and they never let you take it back. "Actually I did buy a bottle of wine this week, .1 just remembered," I coyly added after being rejected. I was not even given the courtesy of a response as the dial tone rang in my ear. Do not be concerned that the phone operator will find you strange for haying purchased every item they list off. -They really couldn't care less. On many occasions they will ask you if you have any friends who would be interested in coming out. Always give them as many names as you can. It never hurts to be nice to people and who knows, maybe your friends will return the favour. One of my friends invented a fictional twin brother and requalified under the inventive alias for the same focus group just one hour later than the one he had signed up for under his |

own name. After finishing the first group, my friend went to the bathroom, put on a backwards Yankees cap, and went right back in. Once you get in, the rest is child's play. The focus group supervisors will explain everything they want you to do in baby speak and they may even do it twice to make sure you understand that you should write your assigned number in the top left-hand corner of the survey sheet beside the word marked "number." It's become almost a social event for my friends and I who now go in-groups and make bets as to who will get out first. We take pleasure in writing down funny answers to the stupid questions that are invariably asked, like, how an image of a certain beverage makes you feel. It's truly amazing that companies are throwing around millions of dollars in these so-called research ventures, where they inter view professional focus group attendees who couldn't care less about the product a company is hawking, even if it's one they use on a regular basis. Michael Dojc is a student at McMaster University and an Intern at the Town Crier in Toronto.

|

Panels

When it is important to collect information on trends, whether with respect to consumer preferences and purchasing behaviour or changes in business climate and opportunities, researchers may decide to set up a panel of individuals which can be questioned or surveyed over an extended period of time.

There are essentially three different types of panels:

The most common uses for panels are

- Trend monitoring and future assessment,

- Test marketing and impact assessment, and

- Priority setting for planning and development.

There are some clear advantages to using panels. These include the fact that recall problems are usually minimized, and that it is even possible to study the attitudes and motivation of non-respondents. However, it must also be recognized that maintaining panels is a constant effort. Since there is a tendency for certain people to drop out (those that are too busy, professionals, senior executives, etc.), this can lead to serious bias in the type of respondent that remains on the panel. Participants can also become too sensitized to the study objectives, and thus anticipate the responses they " should" be giving.

Related Readings (LaPage, W.F. (1994). "Using Panels for Travel and Tourism Research", Ch. 40 in Ritchie and Goeldner; Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

Consumer Panels

When researchers are interested in detailed information about purchasing behaviour or insight into certain leisure activities, they will often resort to panels of consumers. A panel will allow the researcher to track behaviour using the same sample over time. This type of longitudinal research provides more reliable results on changes that occur as a result of life cycle, social or professional status, attitudes and opinions. By working with the same panel members, intentions can be checked against action, one of the more problematic challenges that researchers face when studying planned purchases or intentions to engage in certain behaviour (e.g. going on trips, visiting certain sites, participating in sports, etc.).

But looking at trends is not the only use for panels. They can also provide invaluable insight into product acceptance prior to the launch of a new product or service, or a change in packaging, for instance. Panels, whether formally established or tracked informally through common behaviour (e.g. membership in a club, purchase of a specific product, use of a fidelity card, etc.), can also be used to study the reaction to potential or actual events, the use of promotional materials, or the search for information.

Compared to the depth interview and the focus group, a panel is less likely to exaggerate the frequency of a behaviour or purchase decision, or their brand loyalty. Although panels only require sampling once, maintaining the panel can be both time-consuming and relatively costly as attrition and hence finding replacements can be quite high. In order to allow researchers to obtain more detailed follow-up information from panel members, they are usually paid for their services. At the same time, this can introduce a bias into the panel, since the financial incentive will be more or less important depending on the panelists economic status.

Possibly one of the more interesting advantages of panels is that they can provide significant insight into non-response as well as non-participation or decisions not to purchase a given product.

Related Readings (link to Library. Lapage, W.F., Ch. 40 in Ritchie and Goeldner; Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

The Nominal Group Technique

Originally developed as an organizational planning technique by Delbecq, Van de Ven and Gustafson in 1971, the nominal group technique is a consensus planning tool that helps prioritize issues.

In the nominal group technique, participants are brought together for a discussion session led by a moderator. After the topic has been presented to session participants and they have had an opportunity to ask questions or briefly discuss the scope of the topic, they are asked to take a few minutes to think about and write down their responses. The session moderator will then ask each participant to read, and elaborate on, one of their responses. These are noted on a flipchart. Once everyone has given a response, participants will be asked for a second or third response, until all of their answers have been noted on flipcharts sheets posted around the room.

Once duplications are eliminated, each response is assigned a letter or number. Session participants are then asked to choose up to 10 responses that they feel are the most important and rank them according to their relative importance. These rankings are collected from all participants, and aggregated. For example:

Overall measure

| Response | Participant 1 | Participant 2 | Participant 3 | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | ranked 1st | ranked 2nd | ranked 2nd | 5 = ranked 1st |

| B | ranked 3rd | ranked 1st | ranked 3rd | 7 = ranked 3rd |

| C | ranked 2nd | ranked 3rd | ranked 1st | 6 = ranked 2nd |

| D | ranked 4th | ranked 4th | ranked 4th | 12 = ranked 4th |

Sometimes these results are given back to the participants in order to stimulate further discussion, and perhaps a readjustment in the overall rankings assigned to the various responses. This is done only when group consensus regarding the prioritization of issues is important to the overall research or planning project.

The nominal group technique can be used as an alternative to both the focus group and the Delphi techniques. It presents more structure than the focus group, but still takes advantage of the synergy created by group participants. As its name suggests, the nominal group technique is only "nominally" a group, since the rankings are provided on an individual basis.

Related Readings (Ritchie, J.R.B., E.L., Ch. 42 in Ritchie and Goeldner)

Delphi Technique

Originally developed by the RAND Corporation in 1969 for technological forecasting, the Delphi Method is a group decision process about the likelihood that certain events will occur. Today it is also used for environmental, marketing and sales forecasting.

The Delphi Method makes use of a panel of experts, selected based on the areas of expertise required. The notion is that well-informed individuals, calling on their insights and experience, are better equipped to predict the future than theoretical approaches or extrapolation of trends. Their responses to a series of questionnaires are anonymous, and they are provided with a summary of opinions before answering the next questionnaire. It is believed that the group will converge toward the "best" response through this consensus process. The midpoint of responses is statistically categorized by the median score. In each succeeding round of questionnaires, the range of responses by the panelists will presumably decrease and the median will move toward what is deemed to be the "correct" answer.

One distinct advantage of the Delphi Method is that the experts never need to be brought together physically, and indeed could reside anywhere in the world. The process also does not require complete agreement by all panelists, since the majority opinion is represented by the median. Since the responses are anonymous, the pitfalls of ego, domineering personalities and the "bandwagon or halo effect" in responses are all avoided. On the other hand, keeping panelists for the numerous rounds of questionnaires is at times difficult. Also, and perhaps more troubling, future developments are not always predicted correctly by iterative consensus nor by experts, but at times by "off the wall" thinking or by "non-experts".

Related Readings (link to Library. Moeller, G.H. & Shafer, E.L., Ch. 39 in Ritchie and Goeldner , and Taylor, R.E. & Judd, L.L. (1994). "Delphi Forecasting" in Witt, S.F. & Moutinho, L. Tourism Marketing and Management Handbook. London: Prentice Hall)

Projective Techniques

Deeply held attitudes and motivations are often not verbalized by respondents when questioned directly. Indeed, respondents may not even be aware that they hold these particular attitudes, or may feel that their motivations reflect badly on them. Projective techniques allow respondents to project their subjective or true opinions and beliefs onto other people or even objects. The respondent's real feelings are then inferred from what s/he says about others.

Projective techniques are normally used during individual or small group interviews. They incorporate a number of different research methods. Among the most commonly used are:

- Word association test

- Sentence completion test

- Thematic apperception test (TAT)

- Third-person techniques

While deceptively simple, projective techniques often require the expertise of a trained psychologist to help devise the tests and interpret them correctly.

Related Readings (Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Rotenberg, R.H. (1995). A Manager's Guide to Marketing Research, Toronto: Dryden; Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

Word Association Test

There are a number of ways of using word association tests:

- A list of words or phrases can be presented in random order to respondents, who are requested to state or write the word or phrase that pops into their mind;

- Respondents are asked for what word or phrase comes to mind immediately upon hearing certain brand names;

- Similarly, respondents can be asked about slogans and what they suggest;

- Respondents are asked to describe an inanimate object or product by giving it "human characteristics" or associating descriptive adjectives with it.

For example, a group of tourism professionals working on establishing a strategic marketing plan for their community were asked to come up with personality traits or "human characteristics" for the villages as well as the cities within their area:

Villages

- Serene

- Conservative

- Quaint

- Friendly

- Accessible

- Reliable

Cities

- Brash

- Rushed

- Liberal

- Modern

- Cold

Most of the tourism industry representatives came from the cities and had strongly argued that the urban areas had historically been neglected in promotional campaigns. As a result of this and other exercises, they came to the realization that the rural areas were a strong feature of the overall attractiveness of the destination and needed to be featured as key elements in any marketing campaign.

Related Readings (Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Rotenberg, R.H. (1995). A Manager's Guide to Marketing Research, Toronto: Dryden; Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

Sentence Completion

In the sentence completion method, respondents are given incomplete sentences and asked to complete the thought. These sentences are usually in the third person and tend to be somewhat ambiguous. For example, the following sentences would provide striking differences in how they were completed depending on the personality of the respondent:

"A beach vacation is..."

"Taking a holiday in the mountains is..."

"Golfing is for..."

"The average person considers skiing..."

"People who visit museums are..."

Generally speaking, sentence completion tests are easier to interpret since the answers provided will be more detailed than in a word association test. However, their intent is also more obvious to the respondent, and could possible result in less honest replies.

A variant of this method is the story completion test. A story in words or pictures is given to the respondent who is then asked to complete it in his/her own words.

Related Readings (Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Rotenberg, R.H. (1995). A Manager's Guide to Marketing Research, Toronto: Dryden; Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

Thematic Apperception

In the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), the respondents are shown one or more pictures and asked to describe what is happening, what dialogue might be carried on between characters and/or how the "story" might continue. For this reason, TAT is also known as the picture interpretation technique. (click to view an example)

Although the picture, illustration, drawing or cartoon that is used must be interesting enough to encourage discussion, it should be vague enough not to immediately give away what the project is about.

TAT can be used in a variety of ways, from eliciting qualities associated with different products to perceptions about the kind of people that might use certain products or services.

For instance, respondents were shown a schematic logo (click here) and asked what type of destination would have such a logo, and what a visitor might expect to find. Some of the comments were:

- That makes me think of the garden.

- It is the city in the country, very much so.

- It looks like New York, with the Empire State Building right there.

- Calming, relaxing. There's a tree there so you can see the country-side and you've got the background with the city and the buildings, so it's a regional focus.

Related Readings (Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

Third Person

The third-person technique, more than any other projective technique, is used to elicit deep seated feelings and opinions held by respondents, that might be perceived as reflecting negatively upon the individual. People will often attribute "virtues" to themselves where they see "vices" in others. For instance, when asked why they might choose to go on an Alaskan cruise, the response might be because of the quality of the scenery, the opportunity to meet interesting people and learn about a different culture. But when the same question is asked as to why a neighbour might go on such a cruise, the response could very well be because of "brag appeal" or to show off.

By providing respondents with the opportunity to talk about someone else, such as a neighbour, a relative or a friend, they can talk freely about attitudes that they would not necessarily admit to holding themselves.

The third-person technique can be rendered more dynamic by incorporating role playing or rehearsal. In this case, the respondent is asked to act out the behaviour or express the feelings of the third person. Particularly when conducting research with children, this approach can prove to be very helpful since they "know" how others would act but cannot necessarily express it in words.

Related Readings (Kumar, V., Aaker, D.A. & Day, G.S. (1999). Essentials of Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Zikmund, W.G. (1997). Exploring Marketing Research, 6th edition. Orlando: The Dryden Press)

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is most common encountered as part of formal or conclusive research, but is also sometimes used when conducting exploratory research. Quantitative research techniques are part of primary research.

Quantitative research differs from qualitative research in the following ways:

The data is usually gathered using more structured research instruments

The results provide less detail on behaviour, attitudes and motivation

The results are based on larger sample sizes that are representative of the population,

The research can usually be replicated or repeated, given it high reliability; and

The analysis of the results is more objective.

The most common quantitative research techniques include:

Survey Techniques

The survey technique involves the collection of primary data about subjects, usually by selecting a representative sample of the population or universe under study, through the use of a questionnaire. It is a very popular since many different types of information can be collected, including attitudinal, motivational, behavioural and perceptive aspects. It allows for standardization and uniformity both in the questions asked and in the method of approaching subjects, making it far easier to compare and contrast answers by respondent group. It also ensures higher reliability than some other techniques.

If properly designed and implemented, surveys can be an efficient and accurate means of determining information about a given population. Results can be provided relatively quickly, and depending on the sample size and methodology chosen, they are relatively inexpensive. However, surveys also have a number of disadvantages, which must be considered by the researcher in determining the appropriate data collection technique.

Since in any survey, the respondent knows that s/he is being studied, the information provided may not be valid insofar as the respondent may wish to impress (e.g. by attributing him/herself a higher income or education level) or please (e.g. researcher by providing the kind of response s/he believes the researcher is looking for) the researcher. This is known as response error or bias.

The willingness or ability to reply can also pose a problem. Perhaps the information is considered sensitive or intrusive (e.g. information about income or sexual preference) leading to a high rate of refusal. Or perhaps the question is so specific that the respondent is unable to answer, even though willing (e.g. "How many times during the past month have you thought about a potential vacation destination?") If the people who refuse are indeed in some way different from those who do not, this is knows as a non-response error or bias.Careful wording of the questions can help overcome some of these problems.

The interviewer can (inadvertently) influence the response elicited through comments made or by stressing certain words in the question itself. In interview surveys, the interviewer can also introduce bias through facial expressions, body language or even the clothing that is worn. This is knows as interviewer error or bias.

Another consideration is response rate. Depending on the method chosen, the length of the questionnaire, the type and/or motivation of the respondent, the type of questions and/or subject matter, the time of day or place, and whether respondents were informed to expect the survey or offered an incentive can all influence the response rate obtained. Proper questionnaire design and question wording can help increase response rate.

There are three basic types of surveys:

Please see these excellent articles on survey administration and the right administration method for your research by Pamela Narins from the SPSS website.

Telephone

The use of the telephone has been found to be one of the most inexpensive, quick and efficient ways of surveying respondents. The ubiquity of telephone ownership as well as the use of unlisted numbers are factors that must, however, be considered as part of the sampling frame, even in North America, where the number of households with phones approaches 100%. Telephone surveys also allow for random sampling, allowing for the extrapolation of characteristics from the sample to the population as a whole.

There tends to be less interviewer bias than in interview surveys, especially if the interviewers are trained and supervised to ensure consistent interview administration. The absence of face-to-face contact can also be an advantage since respondents may be somewhat more inclined to provide sensitive information. Further, some people are reluctant to be approached by strangers, whether at their home or in a more public location, which can be overcome by the more impersonal use of the telephone.

On the other hand, telephone surveys are also known to have a number of limitations. The length of the survey has to be kept relatively short to less than 15 minutes as longer interviews can result in refusal to participate or premature termination of the call. The questions themselves must also be kept quite short and the response options simple, since there can be no visual aids such as a cue card.

The increasing use of voice mail and answering machines has made phone surveys more difficult and more costly to undertake. Calls that go answered, receive a busy signal or reach a machine, require callbacks. Usually, eligible respondents will be contacted a pre-determined number of times, before they are abandoned in favour of someone else. The potential for response bias must be considered, however, when discussing the results of a study that relied on the telephone.

The sample for a telephone survey can be chosen by selecting respondents

- from the telephone directory, e.g. by calling every 100th name

- through random-digit dialling (RDD) where the last four digits of a telephone number are chosen randomly for each telephone exchange or prefix (i.e. first three numbers), or

- the use of a table of random numbers.

The importance of randomization is discussed under probability sampling.

Two practices that are increasing in popularity and that raise considerable ethical issues, since the respondents are misled into believing that they are participating in research, are:

- the survey sell (also known as sugging), whereby products or services are sold, and

- the raising of funds for charity (also knows as frogging).

Self-Administered

Any survey technique that requires the respondent to complete the questionnaire him/herself is referred to as a self-administered survey. The most common ways of distributing these surveys are through the use of mail, fax, newspapers/magazines, and increasingly the internet, or through the place of purchase of a good or service (hotel, restaurant, store). They can also be distributed in person, for instance as part of an intercept survey. Depending on the method of survey administration, there are a number of sampling frame considerations, such as who can or cannot be reached by fax or internet, or whether there is a sample bias.

A considerable advantage of the self-administered survey is the potential anonymity of the respondent, which can lead to more truthful or valid responses. Also, the questionnaire can be filled out at the convenience of the respondent. Since there is no interviewer, interviewer error or bias is eliminated. The cost of reaching a geographically dispersed sample is more reasonable for most forms of self-administered surveys than for personal or telephone surveys, although mail surveys are not necessarily cheap.

In most forms of self-administered surveys, there is no control over who actually fills out the questionnaire. Also, the respondent may very well read part or all of the questionnaire before filling it out, thus potentially biasing his/her responses. However, one of the most important disadvantages of self-administered surveys is their low response rate. Depending upon the method of administration chosen, a combination of the following can help in improving the response rate:

- A well written covering letter of appeal, personalized to the extent possible, that stresses why the study is important and why the particular respondent should fill in the questionnaire.

- If respondents are interested in the topic and/or the sponsoring organization, they are more likely to participate in the survey; these aspects should be stressed in the covering letter

- Ensuring confidentiality and/or anonymity, and providing the name and contact number of the lead researcher and/or research sponsor should the respondent wish to verify the legitimacy of the survey or have specific questions

- Providing a due date that is reasonable but not too far off and sending or phoning at least one reminder (sometimes with another survey, in case the original one has been misplaced)

- Follow-up with non-respondents

- Providing a postage paid envelope or reply card

- Providing an incentive, particularly monetary, even if only a token

- A well designed, visually appealing questionnaire

- A shorter questionnaire, where the wording of questions has been carefully considered. For instance, it might start with questions of interest to the respondent, while all questions and instructions are clear and straight forward

- An envelope that is eye-catching, personalized and does not resemble junk mail

- Advance notification, either by phone or mail, of the survey and its intent

Interview

Face-to-face interviews are a direct communication, primary research collection technique. If relatively unstructured but in-depth, they tend to be considered as part of qualitative research. When administered as an intercept survey or door-to-door, they are usually part of quantitative research.

The opportunity for feedback to the respondent is a distinct advantage in personal interviews. Not only is there the opportunity to reassure the respondent should s/he be reluctant to participate, but the interviewer can also clarify certain instructions or questions. The interviewer also has the opportunity to probe answers by asking the respondent to clarify or expand on a specific response. The interviewer can also supplement answers by recording his/her own observations, for instance there is no need to ask the respondent’s gender or the time of day/place where the interview took place.

The length of interview or its complexity can both be much greater than in other survey techniques. At the same time, the researcher is assured that the responses are actually provided by the person intended, and that no questions are skipped. Referred to as item non-response, it is far less likely to occur in personal interviews than in telephone or self-administered surveys. Another distinct advantage of this technique is that props or visual aid can be used. It is not uncommon, for instance, to provide a written response alternatives where these are complex or very numerous. Also, new products or concepts can be demonstrated as part of the interview.

Personal interviews provide significant scope for interviewer error or bias. Whether it is the tone of voice, the way a question is rephrased when clarified or even the gender and appearance of the interviewer, all have been shown to potentially influence the respondent’s answer. It is therefore important that interviewers are well trained and that a certain amount of control is exercised over them to ensure proper handling of the interview process. This makes the interview survey one of the most costly survey methods.

Although the response rate for interviews tends to be higher than for other types of surveys, the refusal rate for intercept survey is higher than for door-to-door surveys. Whereas the demographic characteristics of respondents tend to relatively consistent in a geographically restricted area covered by door-to-door surveys, intercept surveys may provide access to a much more diversified group of respondents from different geographic areas. However, that does not mean that the respondents in intercept surveys are necessarily representative of the general population. This can be controlled to a certain extent by setting quota sampling. However, intercept surveys are convenience samples and reliability levels can therefore not be calculated. Door-to-door interviews introduce different types of bias, since some people may be away from home while others may be reluctant to talk to strangers. They can also exclude respondents who live in multiple-dwelling units, or where there are security systems limiting access.

Quota Sampling

In quota sampling, the population is first segmented into mutually exclusive sub-groups, just as in stratified sampling. Then judgement is used to select the subjects or units from each segment based on a specified proportion. It is this second step which makes the technique one of non-probability sampling.

Let us assume you wanted to interview tourists coming to a community to study their activities and spending. Based on national research you know that 60% come for vacation/pleasure, 20% are VFR (visiting friends and relatives), 15% come for business and 5% for conventions and meetings. You also know that 80% come from within the province. 10% from other parts of Canada, and 10% are international. A total of 500 tourists are to be intercepted at major tourist spots (attractions, events, hotels, convention centre, etc.), as you would in a convenience sample. The number of interviews could therefore be determined based on the proportion a given characteristic represents in the population. For instance, once 300 pleasure travellers have been interviewed, this category would no longer be pursued, and only those who state that one of the other purposes was their reason for coming would be interviewed until these quotas were filled.

Obvious advantages of quota sampling are the speed with which information can be collected, the lower cost of doing so and the convenience it represents.

Convenience Sampling

In convenience sampling, the selection of units from the population is based on easy availability and/or accessibility. The trade-off made for ease of sample obtention is the representativeness of the sample. If we want to survey tourists in a given geographic area, we may go to several of the major attractions since tourists are more likely to be found in these places. Obviously, we would include several different types of attractions, and perhaps go at different times of the day and/or week to reduce bias, but essentially the interviews conducted would have been determined by what was expedient, not by ensuring randomness. The likelihood of the sample being unrepresentative of the tourism population of the community would be quite high, since business and convention travellers are likely to be underrepresented, and – if the interview was conducted in English – non-English speaking tourists would have been eliminated.

Therefore, the major disadvantage of this technique is that we have no idea how representative the information collected about the sample is to the population as a whole. But the information could still provide some fairly significant insights, and be a good source of data in exploratory research.

Validity

Validity determines whether the research truly measures that which it was intended to measure or how truthful the research results are. In other words, does the research instrument allow you to hit "the bull’s eye" of your research object? Researchers generally determine validity by asking a series of questions, and will often look for the answers in the research of others.

Starting with the research question itself, you need to ask yourself whether you can actually answer the question you have posed with the research instrument selected. For instance, if you want to determine the profile of Canadian ecotourists, but the database that you are using only asked questions about certain activities, you may have a problem with the face or content validity of the database for your purpose.

Similarly, if you have developed a questionnaire, it is a good idea to pre-test your instrument. You might first ask a number of people who know little about the subject matter whether the questions are clearly worded and easily understood (whether they know the answers or not). You may also look to other research and determine what it has found with respect to question wording or which elements need to be included in order to provide an answer to the specific aspect of your research. This is particularly important when measuring more subjective concepts such as attitudes and motivations. Sometimes, you may want to ask the same question in different ways or repeat it at a later stage in the questionnaire to test for consistency in the response. This is done to confirm criterion validity. All of these approaches will increase the validity of your research instrument.

Probing for attitudes usually requires a series of questions that are similar, but not the same. This battery of questions should be answered consistently by the respondent. If it is, the scale items are said to have high internal validity.

What about the sample itself? Is it truly representative of the population chosen? If a certain type of respondent was not captured, even though they may have been contacted, then your research instrument does not have the necessary validity. In a door-to-door interview, for instance, perhaps the working population is severely underrepresented due to the times during which people were contacted. Or perhaps those in upper income categories, more likely to live in condominiums with security could not be reached. This may lead to poor external validity since the study results are likely to be biased and not applicable in a wider sense.

Most field research has relatively poor external validity since the researcher can rarely be sure that there were no extraneous factors at play that influenced the study’s outcomes. Only in experimental settings can variables be isolated sufficiently to test their impact on a single dependent variable.

Although an instrument’s validity presupposes that it has reliability, the reverse is not always true. Indeed, you can have a research instrument that is extremely consistent in the answers it provides, but the answers are wrong for the objective the study sets out to attain.

Reliability

The extent to which results are consistent over time and an accurate representation of the total population under study is referred to as reliability. In other words, if the results of a study can be reproduced under a similar methodology, then the research instrument is considered to be reliable.

Should you have a question that can be misunderstood, and therefore is answered differently by respondents, you are dealing with low reliability. The consistency with which questionnaire items are answered can be determined through the test-retest method, whereby a respondent would be asked to answer the same question(s) at two different times. This attribute of the instrument is actually referred to as stability. If we are dealing with a stable measure, then the results should be similar. A high degree of stability indicates a high degree of reliability, since the results are repeatable. The problem with the test-retest method is that it may not only sensitize the respondent to the subject matter, and hence influence the responses given, but that we cannot be sure that there were no changes in extraneous influences such as an attitude change that has occurred that could lead to a difference in the responses provided.

Probing for attitudes usually requires a series of questions that are similar, but not the same. This battery of questions should be answered consistently by the respondent. If it is, the instrument shows high consistency. This can be tested using the split-half method, whereby the researcher takes the results obtained from one-half of the scale items and checks them against the results of the other half.

Although the researcher may be able to prove the research instrument’s repeatability and internal consistency, and therefore reliability, the instrument itself may not be valid. In other words, it may consistently provide similar results, but it does not measure what the research proposed to determine.

Questionnaire Design and Wording

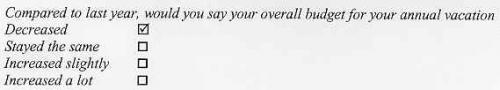

The questionnaire is a formal approach to measuring characteristics, attitudes, motivations, opinions as well as past, current and possible future behaviours. The information produced from a questionnaire can be used to describe, compare or predict these facts. Depending on the objectives, the survey design must vary. For instance, in order to compare information, you must survey respondents at least twice. If you are comparing travel intentions and travel experience, you would survey respondents before they leave on vacation and after they return to see in which ways their perceptions, opinions and behaviours might have differed from what they thought prior to experiencing the destination.

Everything about a questionnaire – its appearance, the order the questions are in, the kind of information requested and the actual words used – influences the accuracy of survey results. Common sense and good grammar are not enough to design a good questionnaire! Indeed, even the most experienced researchers must pre-test their surveys in order to eliminate irrelevant or poorly worded questions. But before dealing with the question wording and design and layout of a questionnaire, we must understand the process of measurement.

Measurements and Scaling

The first determination in any survey design is "What is to be measured?" Although our problem statement or research question will inform us as to the concept that is to be investigated, it often does not say anything about the measurement of that concept. Let us assume we are evaluating the sales performance of group sales representatives. We could define their success in numerical terms such as dollar value of sales or unit sales volume or total passengers. We could even express it in share of sales or share of accounts lost. But we could also measure more subjective factors such as satisfaction or performance influencers.

In conclusive research, where we rely on quantitative techniques, the objective is to express in numeric terms the difference in responses. Hence, a scale is used to represent the item being measured in the spectrum of possibilities. The values assigned in the measuring process can then be manipulated according to certain mathematical rules. There are four basic types of scales which range from least to most sophisticated for statistical analysis (this order spells the French word "noir"):

Nominal Scale

Some researchers actually question whether a nominal scale should be considered a "true" scale since it only assigns numbers for the purpose of catogorizing events, attributes or characteristics. The nominal scale does not express any values or relationships between variables. Labelling men as "1" and women as "2" (which is one of the most common ways of labelling gender for data entry purposes) does not mean women are "twice something or other" compared to men. Nor does it suggest that 1 is somehow "better" than 2 (as might be the case in competitive placement).

Consequently, the only mathematical or statistical operation that can be performed on nominal scales is a frequency run or count. We cannot determine an average, except for the mode – that number which holds the most responses - nor can we add and subtract numbers.

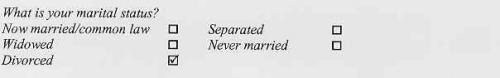

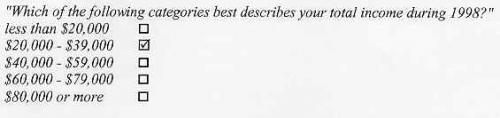

Much of the demographic information collected is in the form of nominal scales, for example:

In nominal scale questions, it is important that the response categories must include all possible responses. In order to be exhaustive in the response categories, you might have to include a category such as "other", "uncertain" or "don’t know/can’t remember" so that respondents will not distort their information by trying to forcefit the response into the categories provided. But be sure that the categories provided are mutually exclusive, that is to say do not overlap or duplicate in any way. In the following example, you will notice that "sweets" is much more general than all the others, and therefore overlaps some of the other response categories:

Which of the following do you like: (check all that apply):

| Chocolate o | Pie o |

| Cake o | Sweets o |

| Cookies o | Other o |

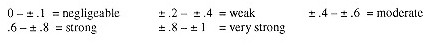

Ordinal Scale