Incidental Trichinella-type parasite in a canine eyelid biopsy for Meibomian gland adenoma excision

Rebecca Egan, César Rodríguez

Animal Health Laboratory, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON (Egan); Englehart Animal Hospital, Englehart ON (Rodríguez)

AHL Newsletter 2024;28(1):33.

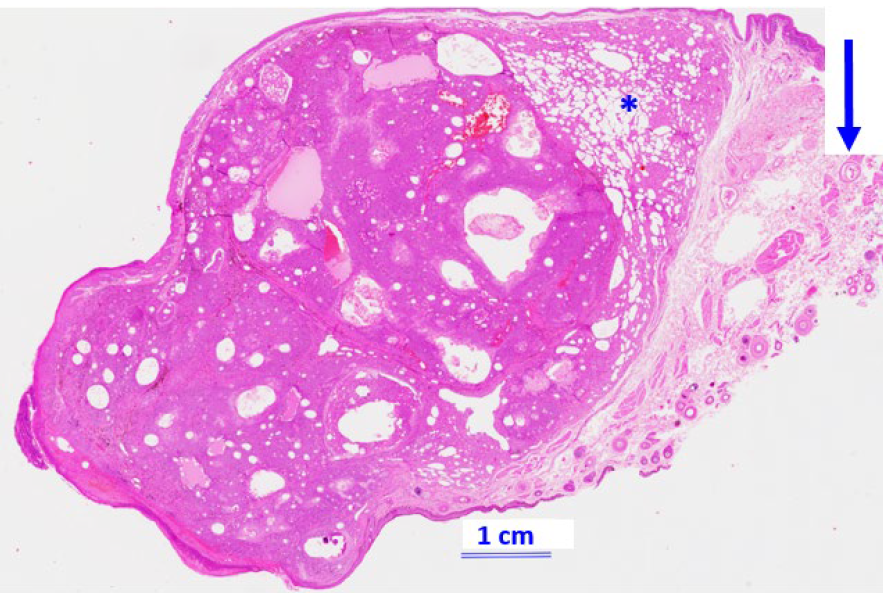

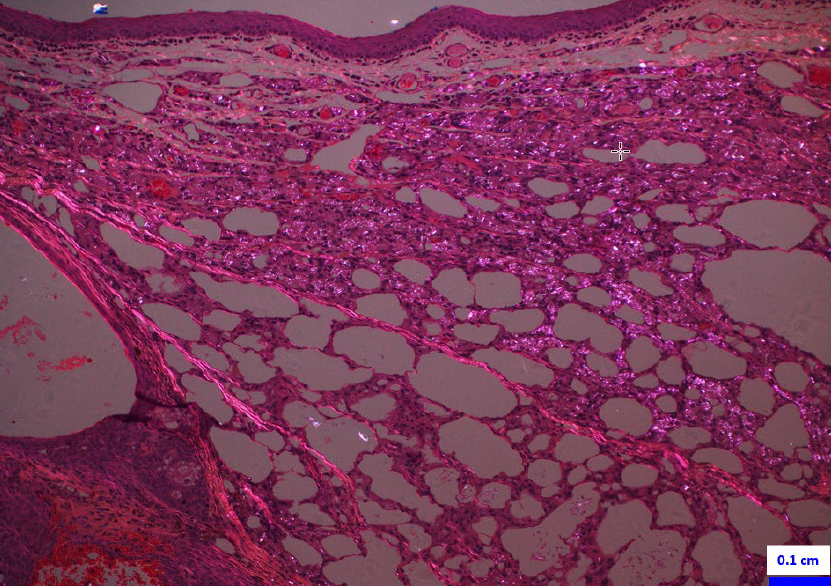

A 14-year-old male neutered Shih Tzu dog presented to his veterinarian in Northern Ontario for assessment of a 1 cm diameter mass on the right lower eyelid. The mass had been present for 1.5 years and had been growing slowly until a recent rapid increase in size was noted. An excisional biopsy of the eyelid mass was performed, along with a dental cleaning and extractions in the face of grade IV periodontal disease with concurrent neutrophilia. The eyelid specimen was sent to the Animal Health Laboratory for histopathology, and microscopic examination revealed a well-circumscribed 6 x 4 mm Meibomian gland adenoma expanding the skin at the mucocutaneous junction of the eyelid (Fig. 1). In the conjunctiva and dermis immediately surrounding the mass were lipid lakes and accumulations of macrophages that contained ample cytoplasm with many pieces of linear birefringent material (Fig. 2).

This type of inflammation is characteristic of a chalazion which is a focus of lipogranulomatous inflammation incited by leakage of secretory material from a Meibomian gland adenoma. This inflammatory reaction likely contributed to the recent rapid growth noted clinically.

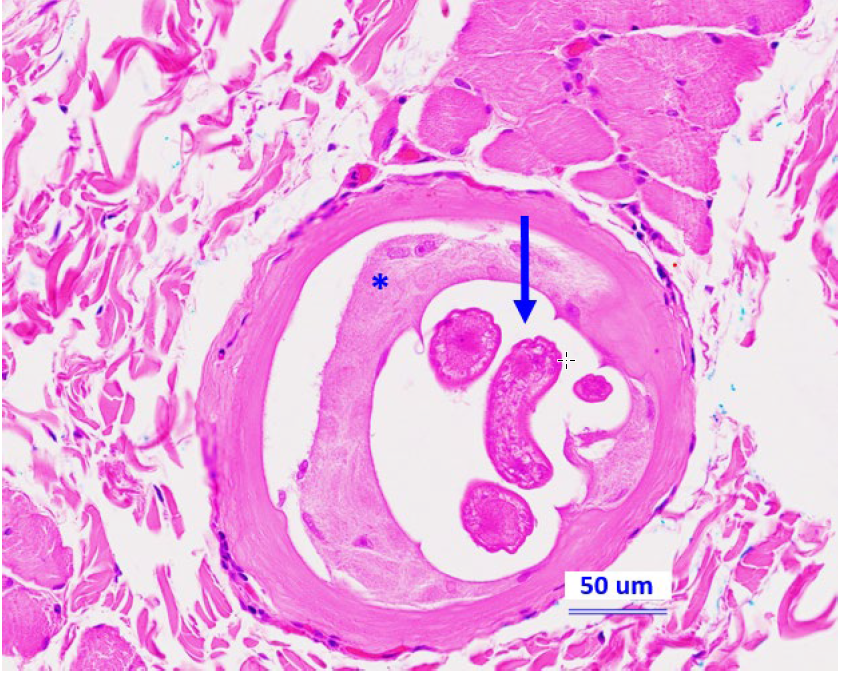

Microscopic examination of this specimen also revealed an unexpected finding. In the striated muscle of the eyelid adjacent to the mass, there was one enlarged myocyte with accumulation of fibrillar eosinophilic cytoplasm and multiple vesicular nuclei (nurse cell) surrounding a central intra-sarcoplasmic nematode larva typical of a Trichinella spp. parasite (Fig. 3). Diagnostic testing to confirm the species of parasite was not feasible, as only formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue was available, and fresh muscle tissue is required for the standard muscle digestion test used for identification of this parasite.

Establishment of Trichinella spp. infection occurs following ingestion of meat harbouring parasitic cysts, with larvae eventually migrating throughout the body and forming intramuscular cysts in the host. These larval cysts may remain viable for years with no clinical signs of disease, therefore the majority of most infections in domestic and wild animals are likely to go undiagnosed. Interestingly, there is one recent European study where serologic assessment has been developed to utilize hunting dogs as a sentinel to monitor Trichinella spp. infections wildlife populations. In this dog, the precise source of the parasitic infection was unclear, but hunting of small rodents or consumption of a raw food diet were considered. The dog had been living in Northern Ontario in a rural setting close to farms and wooded areas for approximately 12 years, and while raw meat was not provided in the animal’s diet at home and the dog had a primarily indoor life, scavenging of small rodents such as mice was a possibility. This dog had been acquired by the owners later in his life as a rescue, so the dog’s lifestyle and exposure to wildlife prior to this period are unknown. AHL

Figure 1. Microscopic section of eyelid (H&E, 1x) capturing an expansile Meibomian gland adenoma at the mucocutaneous junction accompanied by adjacent lipogranulomatous inflammation known as chalazion (*), and nearby striated muscle where there is a parasitic structure within a myocyte (arrow).

Figure 2. Microscopic section of eyelid (H&E, 10x, polarized light) capturing the chalazion, characterized by lipogranulomatous inflammation with linear birefringent material within the cytoplasm of macrophages (*).

Figure 3. Microscopic section of eyelid (H&E, 20x) capturing a nematode larva (arrow) in a myocyte with nurse cell formation (*) compatible with Trichinella spp.

References

1. Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. (eds.). An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. 64 pp. American Registry of Pathology, Washington, DC, 1999.

2. Gómez-Morales MA, Selmi M, Ludovisi A, et al. Hunting dogs as sentinel animals for monitoring infections with Trichinella spp. in wildlife. Parasites Vectors 2016;9:154.

3. Gottstein B, Pozio E, Nöckler K. Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control of trichinellosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2009;22:127–45.