Lung fluke (Paragonimus kellicotti) infection in dogs and cats

Maureen E. C. Anderson, Margaret Stalker

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (Anderson), Animal Health Laboratory (Stalker), University of Guelph, Guelph, ON

AHL Newsletter 2022;26(2):26.

In late 2021, several cases of lung fluke infection in dogs from the eastern shore of Lake Huron, ON area were reported to the OAHN Companion Animal Network. In North America, the most common lung fluke affecting dogs and cats is the trematode Paragonimus kellicotti. This species is found throughout the Mississippi and Great Lakes waterways. Several other Paragonimus species endemic to China, Southeast Asia, Japan, Central and South America can also infect pets. A search of case records from the AHL database (2007 – 2022) revealed 12 positive fecal samples for Paragonimus eggs, 3 from cats, 9 from dogs. In addition, there were 2 pathology cases in dogs with spontaneous pneumothorax, with the fluke/eggs visualized in lung biopsy samples (Fig. 1).

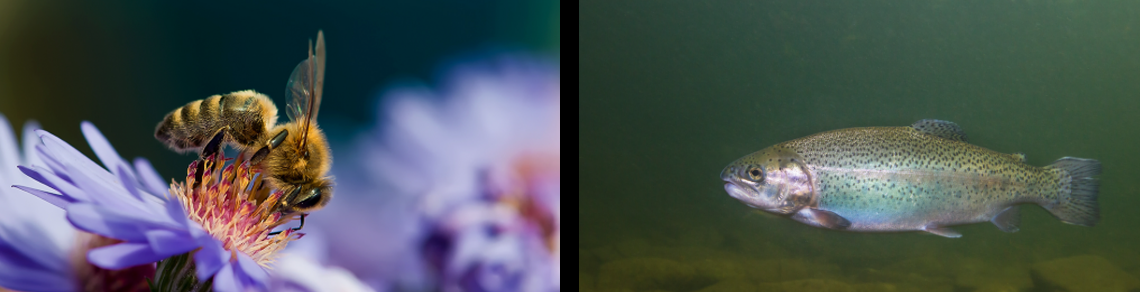

The natural definitive host of P. kellicotti is wild mink. Infected mink pass fluke eggs in their feces. Once in an aquatic environment, the parasite follows a complex life cycle involving aquatic snails as the first intermediate host, and freshwater crayfish as the second intermediate host. Immature forms can also survive free in water for days. Mink, as well as other animals including cats, dogs, and very rarely, people, can become infected by eating raw (or undercooked) crayfish, or eating other small animals (e.g., rodents) that feed on crayfish and act as paratenic hosts. Pets cannot spread the parasite directly to humans. Once ingested, the immature flukes are released and migrate from the intestinal tract through the body cavities until they reach the lungs, where they mature into adults and form cysts in the bronchioles after 2-3 weeks. Fluke eggs are coughed up, swallowed and passed in the feces. The prepatent period in cats is approximately 5-7 weeks.

Clinical signs of infection can range from none, or a mild cough, to varying degrees of dyspnea. In severe cases, animals may develop bronchiectasis, hemoptysis, or spontaneous pneumothorax. Detection of P. kellicotti eggs in the feces typically requires fecal sedimentation, as sensitivity of routine fecal flotation is poor (note: fecal centrifugal sedimentation can be specifically requested at AHL Parasitology, test short code fcsed). Eggs can also be detected on transtracheal wash in some cases. Eggs have a brown shell with a distinct operculum on one end, and are approximately 75-118 um x 42-67 um in size (Fig.1). Cysts in the lungs may be noted on thoracic radiographs or CT, and can be an incidental finding in subclinical cases. The flukes have a predilection for the caudal lobes, particularly the right lung. Peripheral eosinophilia may also be present.

There are no drugs available in Canada or the US with a label claim for treatment of P. kellicotti in dogs or cats; however, praziquantel and fenbendazole are reported to be effective. Treatment with either drug may need to be repeated in some cases to fully eliminate the infection. Treatment with praziquantel PO in cats can be problematic due to the bitter taste of some formulations, and may be cost-prohibitive in large dogs. Treatment is recommended even in subclinical cases due to the risk of the infection leading to acute pneumothorax. Uncomplicated infections generally respond well to antiparasitic treatment. In severe cases, lung lobectomy may be required.

A veterinary infosheet on P. kellicotti is available from the OAHN Companion Animal Network https://www.oahn.ca/resources/paragonimus-kellicotti/

Figure 1. Histologic view of part of an adult fluke within the bronchiole of an infected dog, showing the thick outer eosinophilic tegument with short spines, and subtegmental musculature. A partially-ruptured, yellow-brown operculate egg is free within the adjacent inflammatory cell debris within the lumen of the bronchiole. This dog developed spontaneous pneumothorax, and a lung lobectomy was performed and submitted for histology. H&E stain.

References

1. https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/lung-fluke-infections-in-dogs

3. https://www.aavp.org/wiki/trematodes-2/trematodes-lungs/paragonimus-kellicotti/

4. Peregrine AS, et al. Paragonimosis in a cat and the temporal progression of pulmonary radiographic lesions following treatment. JAAHA 2015;50:356-60.