Molecular and Cellular Biology researchers develop new way to model gut microbiome in lab settings by adding viruses back in

Research on microbiomes —the communities of microorganisms living in a variety of environments, including the human body, soils and oceans— has grown rapidly in recent years. These studies are advancing our understanding of the role of microbiomes in a variety of human diseases, including intestinal diseases and mental health disorders, as well as their impact in agriculture, natural ecosystems and industry.

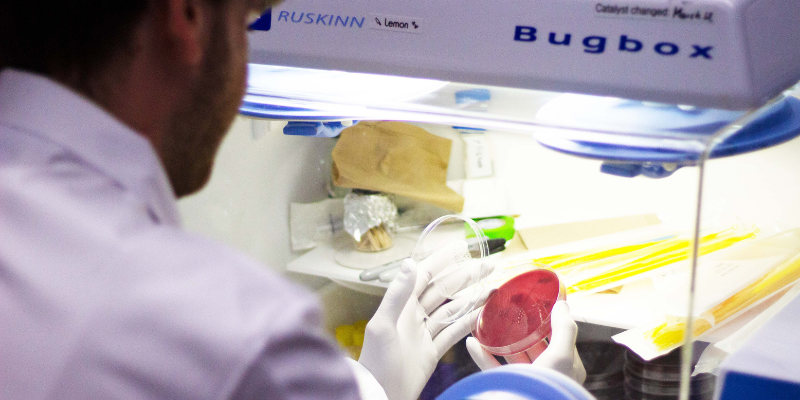

In the lab, microbiologists study these communities by cultivating microorganisms inside bioreactors or mice, but the process of building a synthetic microbiome isn’t perfect. To study the human gut microbiome, for instance, researchers dilute a fecal sample containing billions of bacteria down to a few dozen bacterial cells. This process often leaves out bacteria-infecting viruses, a natural part of most people’s gut microbiome, since there are far fewer of them than bacteria.

While the role of viruses in the gut microbiome is not well understood, a bacterial community without viruses might behave differently than one with viruses – and that difference could impact how scientists learn about microbiomes using synthetic models.

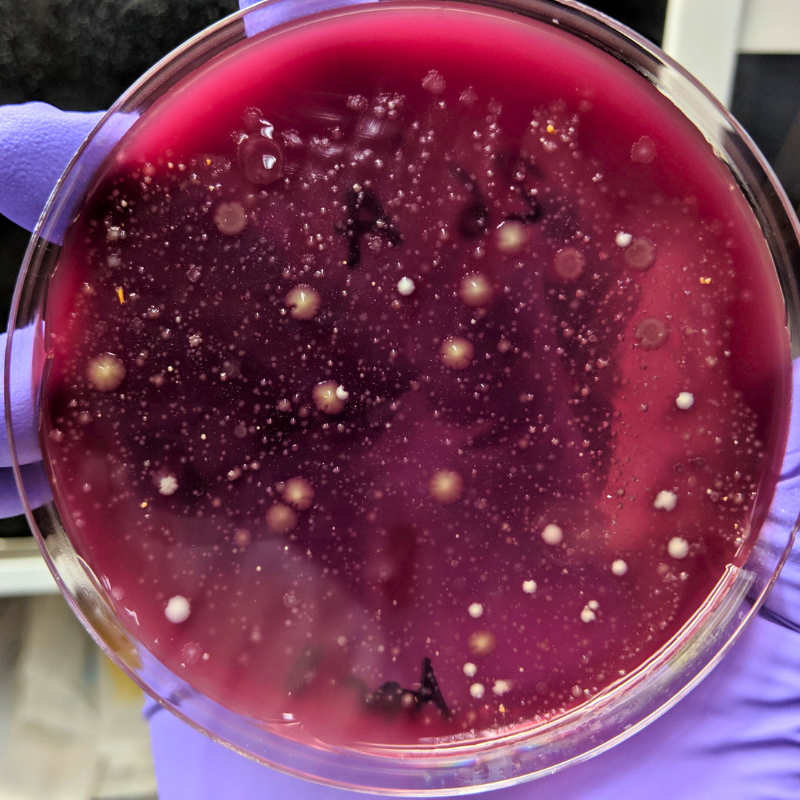

In a study led by recent graduate Dr. Jacob Wilde from Dr. Emma Allen-Vercoe’s lab in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, researchers developed a method of isolating these viruses, known as bacteriophages, and reintroducing them into synthetic microbiomes. They then studied the impact of this reintroduction on the bacterial community, looking at the effect on bacterial composition, metabolism and waste, as well as the impact on any dormant viruses within the bacteria. They found that the reintroduction method impacted all three of these aspects, though the effects seemed to be focused on only those bacterial species that were targeted by the viruses.

In a study led by recent graduate Dr. Jacob Wilde from Dr. Emma Allen-Vercoe’s lab in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, researchers developed a method of isolating these viruses, known as bacteriophages, and reintroducing them into synthetic microbiomes. They then studied the impact of this reintroduction on the bacterial community, looking at the effect on bacterial composition, metabolism and waste, as well as the impact on any dormant viruses within the bacteria. They found that the reintroduction method impacted all three of these aspects, though the effects seemed to be focused on only those bacterial species that were targeted by the viruses.

By building better models of real-world microbiomes, researchers can gain a more accurate understanding of how these microorganism communities function, both in the human body and the environment. The methodology will also be useful for researchers interested in isolating and studying viruses on their own.

“We don’t fully understand the role of viruses in the gut microbiome,” says Wilde. “We know there are some people who have microbiomes but don’t have a lot of viruses, or don’t have a lot of a specific type. Understanding what these viruses do is really important, especially if we want to someday manipulate our microbiomes for better health.”

In the future, Wilde hopes to study how microbiomes evolve in the presence or absence of viruses. In particular, he’s interested in how bacteriophages and human antibodies might compete to bind with the same proteins on bacteria in our intestines, which might put conflicting evolutionary pressures on bacteria.

Wilde plans to continue studying how bacteria evolve as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford in England.

“Assessing phage-host population dynamics by reintroducing virulent viruses to synthetic microbiomes” was published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.