Fit for a female: The impact of housing on mating success in zebrafish

Did you know that fish can tell how each other were raised?

A recent study from Dr. Georgia Mason’s lab in the Department of Integrative Biology has found that zebrafish will selectively mate with fish that were raised in “enriched” housing compared to those from barren tanks. It’s the first time that this phenomenon has been observed in fish.

Mason, an award-winning behavioural biologist, has had a life-long interest in the welfare of animals in captivity. It was during her undergraduate degree that she first noticed how many captive animals spent their days pacing – despite the fact they are supposed to be efficient foragers. “It made me wonder, ‘What broke them?’,” recounts Mason.

Now director of the Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare, Mason remains deeply committed to improving animal welfare in settings as diverse as zoos, farms and research labs. And the subjects of her research have been just as diverse, ranging from rats and mice to monkeys and mink.

The latest study represents a relatively new species of interest in the Mason lab: the zebrafish, a small tropical fish that has become a popular research model in many biomedical labs.

A large body of animal behaviour research in multiple species has shown that less-than-optimal housing impacts an animal’s interactions with other members of their species, often leading to harmful behaviours such as pecking and biting, or reduced sociability. It’s even been found to influence mate choice – where males raised in enriched housing are better able to attract mates. But, to date, this particular phenomenon had only ever been observed in mammals.

“Studies have shown that during mate selection, females may be highly attuned to the ‘welfare status’ of their conspecifics based on the quality of their housing. However, no one had investigated whether or not this happens in fish,” says Mason.

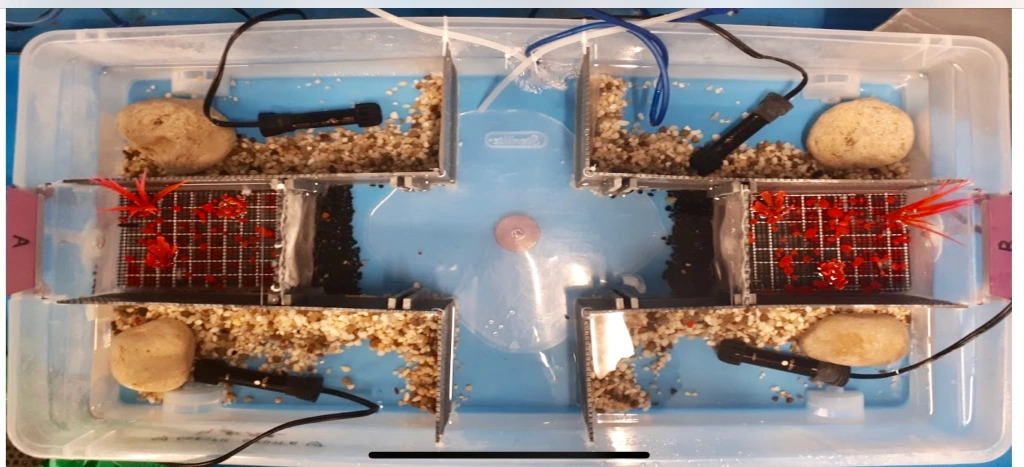

To explore this question, Mason and former PhD student Michelle Lavery set about comparing interactions between females with male zebrafish raised in barren conditions versus those from “well-resourced” tanks. As their name suggests, the barren environments had minimal enrichment, which is typical of the tanks used to house fish for research. The “well-resourced” tanks, on the other hand, were filled with gravel and plants that are known to be preferred by zebrafish.

The first phase of the study involved a female “mate choice test.” Male fish from different rearing environments were held in compartments within the same test arena. A female was then added to the arena and given the opportunity to “approach” the male of her choice – thus indicating her preference.

In the second phase of the study, a female was placed with one male from either type of environment to see what happened when the pair was confined. The researchers then observed each pair for a full 40 minutes to monitor how the females responded to each type of male’s courtship and spawning behaviours.

Overall, the study revealed that female zebrafish do indeed discriminate between males from different housing types. Males from well-resourced housing were approached by females significantly more often than their counterparts from barren conditions. In addition, interactions with males from well-resourced conditions led to females being more receptive to courtship behaviours, as evidenced by fewer attempts by females to escape or to behave aggressively towards the male.

Mason was “pleasantly surprised” by results. “Given that most previous research in this area had focused on rats and mice, we weren’t sure what to expect with fish.”

The study now raises several interesting questions. “For example, we still don’t know how the fish in this study were discriminating between males from different housing conditions. What cues are they using?”

Understanding how housing can influence reproductive interactions in captive fish has several practical applications, such as improving production outcomes in aquaculture hatcheries, and even the success of captive breeding programs for endangered species.

Mason also hopes that the findings will also contribute to a broader understanding of animal welfare in research.

“It’s well-established that enriched housing reduces chronic stress and leads to more natural behaviours in lab animals. That’s not only more humane — it also leads to more valid science.”

Read the full study in the journal Applied Animal Behaviour Science.

Read about other CBS Research Highlights.